Neil Young Chrome Dreams (2023)

From pitchfork.com

One of Neil Young’s most widely bootlegged lost albums from the ’70s gets an official release. As familiar as the material may be, its ragged, magical charm is greater than the sum of its parts.

Sometime after completing Chrome Dreams in early 1977, Neil Young invited his Malibu neighbor Carole King over to hear his latest album. Years later he recalled, “About halfway through she went, ‘Neil, this isn’t an album. It’s not a real album. I mean, there’s nobody playing, and half the songs you’re just doing by yourself.’ She was just laughing at me. Because she crafts albums.”

There’s no way of knowing whether King’s withering assessment of Chrome Dreams played a part in Young’s decision to shelve the album in favor of the charmingly misshapen American Stars ’N Bars in the summer of 1977. Chrome Dreams may have been gone but it wasn’t forgotten. Young lifted four of its tracks wholesale for American Stars ’N Bars, then re-recorded another song for that same album. “Pocahontas” and “Powderfinger” wound up on Rust Never Sleeps, “Captain Kennedy” popped up on Hawks & Doves, and Neil resurrected “Too Far Gone” for his 1989 comeback Freedom. Long before he started excavating lost albums and official bootlegs as part of the Neil Young Archive, Chrome Dreams survived as an acetate that worked its way into the bootleg marketplace, becoming relatively easy to find during the compact disc explosion of the 1990s.

All this subsequent recycling—a practice that ran all the way through 2017, when the late-night session that produced “Pocahontas” and “Captain Kennedy” was released in its entirety as the wistful album Hitchhiker—means that the long-overdue official release of Chrome Dreams carries a vague air of anti-climax. Forget unheard songs: Unlike Homegrown and Toast, two other “lost” albums released under the NYA’s Special Release Series banner, Chrome Dreams barely contains unreleased recordings. The hype sticker attached to the physical edition touts “2 previously unreleased versions,” which amounts to an alternate take of “Hold Back the Tears” and a slow, stumbling early “Sedan Delivery,” which would later take a punishing pace on Rust Never Sleeps.

Disappointing as that may be, Chrome Dreams offers a distinctly different experience than any other Young album from the late 1970s. It serves as an example of how albums manage to be more than the sum of their individual parts. Young is keenly aware how individual songs can harmonize and rhyme. When promoting Chrome Dreams II—a 2007 sequel that bears no overt relation to the album he essayed 30 years earlier—Neil explained, “Quite often I’ll record things that don’t fit with what I’m doing, so I just hold onto them for a while. Some of them are so strong that they destroy what I’m doing. It’s like if you have a bunch of kids and one of them weighs 200 pounds and the other ones are 75 pounds, you’ve got to keep things in order so they don’t hurt each other. So that’s why I held certain things back.”

In a sense, Chrome Dreams is a collection of songs Young held back so they wouldn’t battle with their siblings; he needed to parcel them out in order to give them a fair hearing. When delivered by Crazy Horse in full roar, “Powderfinger” provided Rust Never Sleeps with a clarifying blast of purpose, while “Too Far Gone” benefitted from an older, wearier Neil singing its melancholy refrain nearly 15 years after its original recording. “Captain Kennedy,” a delicate wisp of a song that distinguished Hawks & Doves, offered a bit of a respite in that album’s haphazard clang yet it wasn’t quite at home there. It belongs among its bittersweet companions on Chrome Dreams, a record that very much is a product of Young aimlessly wandering out of the darkness that defined his mid-’70s.

“Captain Kennedy” is an airy recording that shows why Carole King didn’t consider Chrome Dreams “a real album.” Young peppers the record with cuts that contain little more than his voice and a guitar, recordings unadorned by such niceties as harmonies and percussion. Compare “Pocahontas” to its overdubbed incarnation on Rust Never Sleeps: The additional 12-string guitars and airy backing vocals turn a stoned vision into a crystalline fantasy. “Will to Love,” a bizarre reverie where Neil imagines he’s a salmon swimming upstream to mate as he strums his guitar in front of an audibly crackling fireplace, continues these hushed hallucinations. These recordings—not demos, although they’re spare enough to be mistaken for them—give the listener the sense that they’re eavesdropping on Young, a sense of hushed intimacy that suggests Chrome Dreams drifts in a twilight slipstream. It’s a waking dream interrupted by sudden jolts of thunder, as when “Like a Hurricane” blows in after a pensive first act.

“Like a Hurricane” is familiar, particularly this version, which wound up on Decade, the ’77 compilation that consolidated Young’s expeditions into a digestible narrative. Heard within this context, though, “Like a Hurricane” sounds bracing, with the loud, lumbering Crazy Horse sounding cruder than usual when surrounded by contemplative calm. Such shifts in tone aren’t unusual on a Young record, but these particular songs in these particular versions in this particular sequence carry an unusual power. Individually, many of the compositions are indeed the 200-pound titans of Young’s imagination, songs that defined his rich, prolific peak that weathered the years, enduring as core components of his songbook. It would follow that Chrome Dreams also is one of Young’s strongest albums—and it is, yet it also feels curiously amorphous, lacking the ballast of Tonight’s the Night and Rust Never Sleeps. Without an anchor of gravity, Chrome Dreams almost seems to beg to be broken out into segments yet every quivering, ragged rendition of these familiar tunes benefit from being heard in order. What matters are not the parts themselves but how they’re assembled. The connections, both intentional and accidental, are what gives an album its character. Chrome Dreams carries a dream logic that’s bewitching in a way the individual moments simply aren’t, a testament to how a good album sequence can almost be a magic trick.

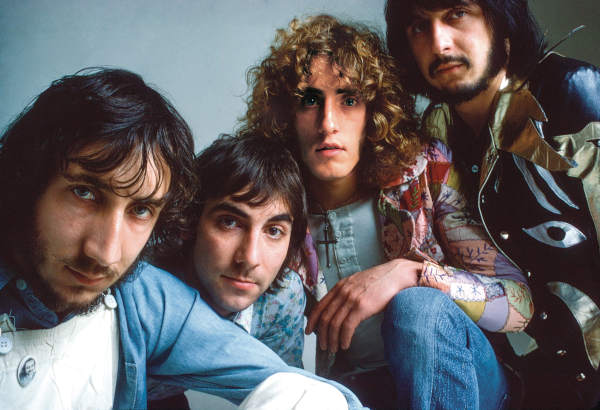

The Who View From A Backstage Pass (2007)

From thewho.info

Live 1970-1974 – not a bootleg

I will break this mini-review into a “Disc 1” and “Disc 2” kinda thing since the material on these discs is from different concerts and each disc has its own “sound and feel” to some extent.

One thing consistent between both discs – I consider these “roughly mixed” vs. “fully mixed” – I’ll try to explain what I mean by that as you read on…

Disc 1 contains primarily tracks from Hull 1970 and San Francisco 1971.

What I found most fascinating were the Hull tracks (Happy Jack, I’m A Boy, A Quick One While He’s Away). The mix sounded nothing like “Keith Moon Band” mix from the 2012 CD (which was also featured on the 2010 “Live At Leeds” box set). The mix was more like Live At Leeds (as it should be), but not as “defined” (or “refined”). I refer to this as a “rough mix” (not to be confused with the Pete Townshend album title) as you can tell someone moved the levers on the mixing board, but didn’t “fine tune it” to perfection.

I actually prefer the “rough mix” of Hull to the “wrong mix” of Hull. Listening to the Hull tracks on this disc was wonderful as opposed to “WTF”? As I was listening to “good Hull” (and enjoying it), I had to wonder the whole time, how they screwed the mix up so badly on the “official Hull”. Was it due to the “taking the bass parts from Leeds” on the first several tracks and as a result, having to mix down the bass for the rest of the concert to make this work?

IF this were true – what a STUPID thing to do! Rather than “import” John Entwistle’s bass from one concert to “complete” another concert for release, but while doing so screw up the entire mix, they would have been better off using Pino Palladino (or an equally talented session bassist – who could copy John’s style and “add the bass back” for those 3-4 tracks).

What’s the lesser of the “evils” ? Replacement bassist for 3-4 tracks and have an otherwise fantastic concert? Or, have “genuine” bass from John Entwistle (from a different concert) on this concert (which is mixed lower than John would ever have played at that period) and have a completely disappointing mix for the rest of the concert (on CD)? The other theory is that someone just wanted a mix of the “Keith Moon Band” and <Riker>’d it up. Crazy, isn’t it?

“Magic Bus” is from Colorado, 1970. I can see why John was “bored” by playing this. I actually liked this version, although it went on and on forever. Very different from Live At Leeds and very different from Dallas ’89. Sort of a long jam, but without the “heavy pounding” that Leeds develops into… You sort of “wait for something to happen” (like “Leeds”) but it never seems to. That’s OK, it’s not “good or bad”, just different.

Onto the San Francisco tracks (I Can’t Explain, Substitute, My Wife, Behind Blue Eyes, Bargain, Baby Don’t You Do It). These tracks are just great. This concert was originally recorded with intention for release, but never happened. Several tracks have been previously released and again, benefit from a more detailed mix (vs. the “rough mix”) – but these don’t sound “bad” in anyway – just not as “refined”. Very listenable, very enjoyable…

Disc 2…

Things start to “fall apart” here…

Where the “rough mix” worked well enough for Disc 1, it doesn’t work well here.

I suspect this is partially due to how some of the material on disc 2 was recorded. The 1973 tracks were recorded by the King Biscuit Flower Hour (The Punk Meets The Godfather, 5:15, Won’t Get Fooled Again) – most of us are familiar with the whole Largo/Philly/Whatever tracks from either “on the air”, Wolfgang’s Vault or (bootlegs). Is this the best thing they have in the vaults from 1973? A person with better attention to detail on the mixing console *may* have made these tapes sound much better = MAYBE. I don’t know. I do know that those particular King Biscuits weren’t recorded as well as they could be.

Charlton 1974 (Young Man Blues, Tattoo, Boris The Spider, Naked Eye/Let’s See Action/My Generation Blues). These tracks seem to vary a bit. I didn’t like the sound of the vocals in “Young Man Blues” and a few of the other tracks. I’m thinking again this “rough mix” doesn’t work well here. To me, if the vocals don’t work, nothing works well. Great performances, but in need of more refinement to put each performance (vocals, drums, bass, guitar) in the proper sound field and order…

The rest of the tracks came from Swansea 1976. These tracks sound about the same as Charlton (above), with the same mixing/refinement issues. I’m thinking if a little more time and effort went into the production of the CD; it may have been “outstanding” versus “questionable”. Personally, I prefer *not* to pick at things and pull them apart. I much rather sit back and “enjoy the music” (like I do for so much of The Who catalog). Things seem to happen to some of these recordings that make no sense (i.e. Hull). Oh well…

BTW – I know I left off comments of the first track, “Fortune Teller” (from Michigan 1969). Why? Once you’ve listened to the Leeds version, is this one any better or significantly different? Nope. Next track for me. Sorry!

Track Listing:

DISC 1: Fortune Teller, Happy Jack, I’m A Boy, A Quick One While He’s Away, Magic Bus, I Can’t Explain, Substitute, My Wife, Behind Blue Eyes, Bargain, Baby You Don’t Do It

DISC 2: The Punk And The Godfather, 5:15, Won’t Get Fooled Again, Young Man Blues, Tattoo, Boris The Spider, Naked Eye/Let’s See Action/My Generation Blues, Squeeze Box, Dreaming From The Waist, Fiddle About, Pinball Wizard, I’m Free, Tommy’s Holiday Camp, We’re Not Gonna Take It, See Me, Feel Me/Listening To You

Jimmy Page on gatekeeping Led Zep, playing the Olympics, and the tribes of Morocco

From Classic Rock May 2022

Interview: We catch up with Jimmy Page to discuss the passing of time, old friends, and why he won’t tell us what he’s doing next

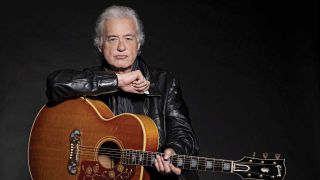

(Image credit: Ross Halfin)

This interview was conducted to mark the 300th issue of Classic Rock magazine, which launched in 1998. The magazine is available to purchase online, and also features interviews with Ozzy Osbourne, Rick Nielsen, Def Leppard, Alice Cooper, Geddy Lee, Slash and many more.

As Classic Rock’s inaugural issue hit newsstands, Jimmy Page was already one of the genre’s most recognised, respected and revered icons. His trailblazing tenure with Led Zeppelin apparently over, he’d recently reconvened with Robert Plant for Unledded and Walking Into Clarksdale’s palate-cleansing reinventions, and was on the cusp of hooking up with The Black Crowes to revisit Zep’s catalogue in significantly rambunctious style.

Twenty-four years later, the recipient of our 2007 Living Legend award pours himself a glass of water to consider his early twenty-first century and his, as yet tantalisingly unwritten, future.

When Classic Rock launched in 1998, the musical landscape was very different to how it is now.

There was a really thriving musical community going on and surprises coming out around that time. People were still pushing their abilities and coming out with great stuff right across the board. The main difference between then and now was that there were a lot of guitar-based bands around.

I was always fascinated to see what people could come up with in that format, because that was always the responsibility I’d given myself, really: to push guitar music in directions that maybe hadn’t been explored before, certainly up until that point in time. So there was a lot of really good stuff going on, but I wouldn’t necessarily know about it, because I was always so deeply involved in what I was doing.

You’d just begun your collaboration with The Black Crowes.

That started at the Café De Paris: I was playing at a charity event for Warchild, and Chris and Rich [Robinson] came along to be part of the band. And my goodness gracious… Rich is massive, his guitar sound and riffs are brilliant, and then you’ve got Chris who is an absolutely amazing vocalist. So just to be jamming with them for that one night was incredible. Rich was just soaring with this improvising and having as good a time as I was. In fact we’re all having a great time and really enjoying it.

So a little later their manager called me up and asked if I’d like to repay the favour by playing with them in the States, so I said I’d love to. Going into rehearsals, I figured I might have to show them how to play this and that, but not a bit of it, they knew the music inside out. I thought: “This is so great, there’s a lot of love and mutual respect here. We’re going to have a great time.” And we did.

Speaking of the Café De Paris, you came along to the first Classic Rock Awards, attended most of them and were honoured as our Living Legend in 2007. What are your memories of those events?

I just remember them being fun. They were tribal, and in a good way. There was a good spirit to it and it was always pretty respectful. The bands that played did a really good job, because it could be a tough audience. It was interesting for me because I’d hear aspects of music I might not have otherwise picked up on, and that’s what it’s all about really. But yeah, it was always fun, and it was lovely to get the Living Legend award in 2007.

They also offered a rare opportunity for old friends to meet up who hadn’t seen each other for an awfully long time. I particularly remember the year when you and Alice Cooper were both there.

When Led Zeppelin went over to play in America we did some dates opening for Vanilla Fudge. The first show we did on our own was at the Whisky A Go Go in LA and Alice Cooper was on the bill. That was in January sixty-nine, so that’s how far back we go. So those Classic Rock Awards really were great tribal gatherings of the clans, a time to meet old pals and to make new ones.

In 1998, did you have any notion that Led Zeppelin might reunite, or did you consider that chapter closed?

In ninety-five, when we toured the Unledded project, the idea was to represent some of the songs in a different way, which we’d do every night when we toured with Led Zeppelin. There was always something different to each number. But to give the material a whole new suit of clothes we applied the orchestra and the Egyptian orchestra along with other exotic sounds, like the hurdy-gurdy player. Robert and I did the lion’s share of the writing in Led Zeppelin, so we were both keen to do something with the two of us, so that’s basically what we did.

You’d also just delivered Walking Into Clarksdale.

The idea of Walking Into Clarksdale was to do an album without the guitar overdubs that I’d usually use for textures and dynamics, just do things with the one guitar. So I took that on as a bit of a challenge, and I thought it was really successful. There were moments of such suspense: Robert’s vocals coming on with the guitar, just a ghosted chord as a song is building toward the chorus… there was really some good work on that album. I really enjoyed both of those projects. And the connection I had with Michael Lee, the drummer was exhilarating and fulfilling in every way really, because there was lots of improvising going on.

When Classic Rock launched, streaming and social media didn’t really exist. Now they’re both an unavoidable part of our lives. When they came along did you welcome or resist them?

When I was with the Crowes, Napster was happening. That’s the first one I was aware of, because scouring the internet isn’t something I did then or do now. I did do a website, because I was doing music no one was going to put out. I wasn’t even going to talk to a record company about it, so the only way to put it out was via a website. Then, more recently, I’ve had an Instagram account that I’ve put a lot of work into and that’s been great fun.

Obviously, downloading and streaming have seriously affected artists’ ability to make money. Do you fear for rock’s future as an economically viable career path for young musicians?

Well, first of all, Tom Gray from Gomez is a hero. He should be on your front page. He’s been lobbying the government to regulate music streaming with his Broken Record campaigning group for the last couple of years, and as a result the government set up a select committee to look into it, and that was an eye-opener. I made a statement because I obviously believe all musicians should be paid for what they do.

There’s also been a massive vinyl resurgence.

Well, I’ve literally never stopped listening to vinyl. I was very disappointed when CDs came out because I didn’t like the sound of them. So much was lost with CDs, and then MP3s, they took so much of the depth, the whole panoramic three-D, or even five-D quality, of the audio experience. So it was great to see the vinyl resurgence. Aside from the sound, there’s the tactile experience, the artwork, liner notes you can read without using a magnifying glass, and the act of actually putting on an album. It’s a lovely little ritual that I never tire of.

You’ve spent an enormous amount of time working on the Led Zeppelin catalogue for the Deluxe Edition reissues.

When CDs first came out the record company started to put out versions of Led Zeppelin albums, and I thought: “My God, I know CDs don’t sound very good, but I know they can sound better than this.” So I went in and supervised the remaster of the whole catalogue so we had proper CDs out there.

I wanted to put out all of the albums, remastered, with a companion disc providing a snapshot of what else was going on in the studio at the time: alternate versions, early generations of mixes, overdubs like that wonderful electronic thing that we created in the middle of Whole Lotta Love that stopped it being a radio single… that was good planning [laughs]. On hearing that track without the overdubs, it’s pure energy. I thought I’d love people to hear this, to show what Led Zeppelin was like in the studio, just how raw and edgy.

What are some of your personal highlights of the past twenty-four years? And have you ever been more self-conscious than when you were standing on top of that bus in Beijing’s Olympic Stadium?

It might sound corny, but that really was a highlight. It was like passing on a relay baton to the next people hosting the Olympics, which was London. People were saying: “Oh, you shouldn’t do that.” And I thought: “Oh, yes I should.”

Those athletes work so hard on getting to the Olympics, focus all their efforts on giving their prime performance on that one day, and I can relate to that. So to be able to do that for the London Olympics would be really great. When they said they wanted the whole full-length version of Whole Lotta Love, I said: “Really? No edits?” “No, really, the full version.” So I said: “Now you’re talking.”

Then when they said Leona Lewis would be singing, I thought: “This is gonna be really interesting.” And boy oh boy, she was really phenomenal. Her vocal was great. I had a great time, and it had the largest audience of anything I’ve ever done.

You could see by the look on your face you were really enjoying it.

It was bloody hot, sitting in the bus waiting for the thing to take you up on the hydraulics, but it went without a hitch and it was fabulous. So that was a high point. Another high point was being represented in the Play It Loud exhibit at New York’s Metropolitan Museum Of Art.

I mean, here’s a kid who started out playing a campfire guitar left behind by the previous occupants of a house where I lived with my parents in Epsom. Then the whole skiffle thing happened, I got a connection with the acoustic guitar, and then there’s everything the electric guitar meant to me.

People who weren’t musicians, rock, rockabilly or blues fans, would look down their noses at solid-bodied guitars. And now, to actually be part of something really heralding the guitar: the physics behind it, the design, its legacy, what it meant to the youth and to musicians, in the Met? That’s the most phenomenal thing.

What have you enjoyed listening to over the past couple of decades?

To be honest, I’ve been really involved in listening to Zep stuff, stuff that preceded The Yardbirds’ stuff. I’ve been archiving, going from analogue to digital. It’s all in real time, so if you’re doing it properly there’s no quick route. You’ve got to listen, make notes, archive efficiently. So I’ve been working on that over a period of decades, finding and revisiting things.

Sometimes I’d go: “Oh, I sort of remember that, but I didn’t realise it was as good as that”, and sometimes: “Why did I do that?” [laughs]. What do I listen to? If you’d asked Jeff Beck in the early days, he’d have said Jimmy has such an eclectic mix of records. And sounds, and I still do. I still listen to all those different genres because I find it gives me so much, it’s like sustenance.

At times, when I’ve felt out of sorts, I just put on the early things that got me hooked. Things like Chuck Berry. The whole attitude of those records, the enthusiasm of what’s being said and the positivity. It doesn’t take long for it to change your frame of mind.

Last time we spoke you told me you didn’t want to waste your time during lockdown. So how have you been occupying yourself over the last couple of years?

Archiving, working on various paths and routes of projects, but I’m not going to say what the projects are. There’s various things I’m working towards. It’s not just one thing, it’s multiple things, and I don’t want to even give a hint, because if you do… You give a one-sentence sound bite, and then if it doesn’t materialise it’s like: “Why didn’t you do a solo album?” So I don’t want to say what it is that I’ve got planned, because I don’t want to give people the chance to misinterpret it.

You only need to look at online forums and it’s clear we’re missing you, Jimmy. And a new record would be a great reward for living through the past few years of madness.

Well, I really can’t put on record what the new record is. I’ll leave it to your imagination. The thing is there are so many ways I could present myself right now. Actually, not right now. I’ll rephrase that: within a space of time [laughs]. I’ve come across all these various projects I did.

And one of the things I did recently is listen to a recording I made of the Marrakesh folk festival, with the tribes coming in from all over Morocco, in 1975. It’s fascinating. Tribal stuff passed on from father to son and kept alive because of the folk festivals, Essaouira, and all the rest. Where there are people who want to hear the Berbers. I certainly do, it’s good for the soul.

You’ve supported Classic Rock magazine from day one. How does it feel to find yourself at issue three hundred?

Well, I’d like to compliment you on the fact Classic Rock has always been a really great magazine. It’s one that I read, and you’ve now come to your three-hundredth issue and need to be congratulated for that. I mean, it’s terrific because it’s physical media, and there it is, on the newsstands. It can be acquired. It’s like me and my vinyl, it’s a tactile thing. And I really like that; I don’t want to see everything on a bloody screen.

I like to hold an instrument and play chords on it, a melody line. It’s the same thing with a book or a magazine. So congratulations on your three hundred, and keep up the good work, because there’s a big audience out there, like me, who really love what you do.

Peter Gabriel i/o (2023)

From pitchfork.com

After two decades of tinkering, the art-rocker’s first album since 2002 arrives in an array of different mixes. Yet the songs are refreshingly uncomplicated, reconnecting with Gabriel’s pop instincts.

If you are someone who struggles with perfectionist tendencies, then you can maybe understand how Peter Gabriel is feeling right now. He has been working on an album called i/o for more than 20 years—and teasing it in the press for even longer—and, as of today, it is finally available to hear in full. But before we listen, we must decide which version of the 12-song album we want to play: the “Bright-Side” or the “Dark-Side” mix, each containing the same tracks in the same order, but featuring small adjustments. And if you check out both and enjoy them well enough, but decide that neither is quite right, then you can opt for the “In-Side” mix, available separately and on the three-disc deluxe edition.

It’s a funny way to place listeners in the shoes of the artist, asking you to consider the tiny tweaks that build a song’s atmosphere and identity. Listening to i/o, you might find yourself asking: Is the trumpet in “Live and Let Live” a crucial component to its climax or a subtle texture in the background? Do the guitars in “Road to Joy” need to blast from the mix or ride alongside the bass groove? You may become frustrated. And Gabriel is right there with you. There he is on the cover—“one of life’s ummer and ahhers,” as his Genesis bandmate Phil Collins once put it—with his head in his hands, fading into a grim, colorless mass.

To even reach this point, the 73-year-old artist had to take some baby steps. First was releasing a new song on each full moon of 2023: a recurring, self-imposed deadline that drip-fed the album steadily to his ever-patient audience. He also booked himself a world tour, where he performed nearly every song from the as-yet-unreleased record each night. Delivered between long monologues about the state of the modern world and the potential benefits of artificial intelligence—and, of course, in between the select hits from his back catalog—Gabriel asked fans to confront this work-in-progress material as a living, breathing art project before encountering it a long-awaited entry in his discography.

Beyond the fact that it actually exists, one of the big surprises of i/o is how uncomplicated it is. His last batch of original songs, 2002’s Up, was dense and depressive, and his orchestral diversions—2010’s covers album Scratch My Back and 2011’s reimagining-the-classics set New Blood—transformed their source material into the kinds of melodramatic slow-burns you hear in trailers for big-budget action films. But i/o reconnects with Gabriel’s pop instincts. For the first time in a long time, he is singing big choruses, writing in simple verse about human nature, and trying to uplift. From the sparse balladry of “So Much” to the horn-accompanied bounce of “Olive Tree,” the music reflects little of its arduous recording process. It sounds natural, intuitive.

Back in 2002, Gabriel introduced the themes of the record as “birth and death and a little bit of in and out activity in between,” which is kind of like saying, “For dinner I’d like something available and edible and tasty.” But he does have a knack for articulating universal experiences in novel ways. “So Much” portrays the scope of our life’s work with two warring sentiments—“So much to aim for” and “Only so much can be done”—while the funky “Road to Joy” offers insight into a raging existential battle: “Just when you think it can’t get worse/The mind reveals the universe.” Other songs tell their story through the arrangements themselves, like the starry, Eno-assisted “Four Kind of Horses” and the steady march of “This Is Home.” With nuanced performances from trusted accompanists like bassist Tony Levin and drummer Manu Katché, you can understand why Gabriel treated these recordings with so much care and attention.

Of course, the long wait and intricate presentation open Gabriel up to some criticism. A lot of the weaknesses come down to the lyrics. When reaching the chorus of the anthemic title track of an album he’s been tinkering away at for so long, could he really not think of a more elegant refrain than “Stuff coming out/Stuff going in”? And in “Live and Let Live,” an empathetic protest song that’s less about world peace than forgiving ourselves, does he really need to invoke an old chestnut about what happens when the whole world takes an eye for an eye? Usually critics hear these types of lyrics and suggest the solution is to spend a little more time in the oven. i/o offers a strong counterargument.

With so much context to consider, it can be easy to take for granted a quality as simple as Gabriel’s voice, which sounds brilliant and remains his defining strength as an artist. What other singer could be equally authoritative delivering one of prog rock’s most notoriously complex concept albums, a couple of the sweetest love songs in rom-com history, the wordless vocal incantations in a Scorsese Bible epic, and angsty Y2K industrial music warranting a Trent Reznor remix? And while many artists Gabriel’s age wind up pivoting to new genres or coating their voice in unearthly effects to accommodate their loss of range, his singing is the most unaffected element of these new songs: bold and melodic, equally clear and prominent in each edition. (For what it’s worth, I prefer the “Dark-Side” mix, which seems more suited to the cohesive full-album experience versus the “Bright-Side,” which caters more to each individual song.)

As history leaves the long rollout in the dust, I imagine his singing will be the quality that distinguishes i/o: a reminder that, for all the endless stress, our simple emotional connections are what perseveres. And, what do you know, this is precisely the subject of the best song on the record, which is called “Playing for Time.” A piano ballad inspired by Randy Newman, it squarely addresses the aging process, how our race against the clock gives us both an increased sense of urgency and a stronger appreciation of the present. Gabriel sings from a zoomed-out perspective about our time on Earth (“There’s a planet spinning slowly/We call it ours”) and the shifting relationships among family members (“The young move to the center/The mom and dad, the frame”). The arrangement is beautiful and precise and a little heavy-handed after the drums come in, but it’s easy to forgive once you lock into the earnest beauty of the words, the tender pull of his delivery. “Any moment that we bring to life—ridiculous, sublime,” he sings, first bellowing then softening his delivery, as if to only remind himself.

The Orb/David Gilmour Metallic Spheres (2010)

From pitchfork.com/

Over the past few years, the Orb have been nudging their sound back toward its techno-hippie roots; now they team with Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour

The Orb have never hidden their art-rock leanings. Their debut album, released in 1991, was a double-vinyl epic entitled, with a knowing nod to the bongs-and-blacklights crowd, Adventures Beyond the Ultraworld. Despite being marketed as house music, Ultraworld was really designed to flow like those spacey prog-song suites that so captivated stoned 70s kids who gorged on sci-fi novels. (The Orb just ditched the “songs” part of the suite equation.) And though the rhythms on the new Metallic Spheres occasionally recall techno and hip-hop and other more recent inventions, this albums sounds a hell of a lot like it could have been playing in a planetarium circa 1974.

Again, as much of that is due to the Orb as to special guest legend David Gilmour of Pink Floyd. The Orb’s music got chillier, tighter, and altogether less shaggy as we moved away from rave’s sloppy love-in and toward the precision-tooled club music of the 21st century. But over the past few years, Orb co-founder Alex Paterson has been gently nudging the group’s sound back toward its techno-hippie roots. Collaborating with Gilmour feels in some ways like the Orb’s coming home after a good many years spent wandering the post-rave wilderness. Their last few albums have sounded as if the band were wondering where exactly they could take their music next, while not quite sure if they truly wanted to revert to their old sound, and the master’s presence feels like it gave the disciples license to go all-out retro.

Mostly wordless, full of spaced-out sound effects, and making no concessions to good ol’ verse-chorus-verse structures, Spheres is a trip, to use a term once unabashedly uttered by Floyd devotees and revived by Orb aficionados with more of a knowing wink. A headphones record, in other words. Light show and chemical refreshment totally optional. Over two long tracks subdivided into shorter movements, Paterson and fellow Orb-er Youth thread together a post-rave library’s worth of slow-rolling chillout-room rhythms, referencing everything from dub to krautrock along the way, as Gilmour sweeps in and out on guitar, dropping little shiver-inducing melodic runs like it’s no big deal. Though his playing here meanders by design, Gilmour sounds neither lazy nor indulgent, more like a virtuoso who doesn’t want to actually seem like he’s sleepwalking through his performance. The Orb, on the other hand, are showing off in the best way possible, again crafting the lush, cosmic rhythms they were once so good at, hoping to impress a long-time hero. In the process, they also manage to impress listeners who’ve stuck with the band through some pretty ropey recent material.

Records like Spheres usually get filed as “ambient” these days, but that’s not quite right here. Sure, it’s gorgeous and hypnotic and more about beats than songs and all the things you’d probably expect from this pairing. It’s also immersive in an old-school way, a long-player of a very pre-digital vintage, a record for people with enough free time (or a long enough commute) to lose themselves in a 50ish-minute composition. With its dramatically orchestrated peaks and valleys, it’s an album designed to be listened to, to Take You Somewhere as you lay on your bedroom floor, to conjure futuristic images in the mind’s eye of folks who were once teenage fans. In that sense, it’s still not quite as successful as the Orb’s classic material, and a little too subdued, lacking both the goofy sampleadelic grandeur and the ear-grabbing pop pulse of the Ultraworld era. But it’s still the most focused and listenable Orb album in years. And hey, if you want to treat it as background music, that’ll work just fine, too.

Saucer Full Of Sour Milk: Roger Waters’ Dark Side Of The Moon Redux (2023)

From thequietus.com/

If there is one thing that ruins Roger Waters’ rerecording of Dark Side Of The Moon – Roger Waters’ Dark Side Of The Moon Redux – then it’s Roger Waters, finds JR Moores

Back in the pre-poptimism heyday of music journalism when people still cared about what kind of crap was being peddled to hapless consumers, musicians were sometimes asked to justify themselves. Interviewing stars for Smash Hits or Q magazine, the legendary Tom Hibbert (1952 – 2011) liked to, as one obituary put it, “give his subjects the impression that, despite their obvious successes, they were still somehow shameful underachievers, and then sit back quietly with a cigarette to enjoy the panicked response.

He sounds a bit like the Grub Street equivalent of The Inquisitor from the sci-fi sitcom Red Dwarf, a terrifying character that continues to haunt the ongoing existential crises of those who were unfortunate enough to watch the show’s fifth series at an impressionable age. In Episode Two, the crew of the titular spaceship encounter a droid who has survived until the end of time, discovered that there is no God or afterlife, and so the sole purpose in life is to make it worthwhile. The droid then roams eternity to visit every individual throughout history and assess each one accordingly. Those unable to justify their existence, who are deemed to have wasted their lives, are erased by The Inquisitor and replaced by other beings who never had the opportunity. “The unfertilised eggs,” as the mechanoid Kryten explains. “The sperms that never made it.”

Speaking of which, Roger Waters has spaffed out a new version of The Dark Side Of The Moon. Now there’s someone who wouldn’t break into a sweat were The Inquisitor to knock on the door of his Hamptons palace. This is the bloke who was described by writer and director Nigel Lesmoir-Gordon as having too much self-importance to appreciate the ego-diminishing experience of LSD. Waters could point The Inquisitor towards the many platinum discs lining the walls of his endless corridors. He could recall flying in the face of punk by releasing one of the most bloated albums ever made to astronomical success in 1979. He could note the joy his palatable arena prog has brought to countless baby boomers over the decades and occasionally some younger listeners. Additionally he could draw attention to his earnest global activities, such as sticking it to Israel and being one of the few voices in the West to defend the reputation of vulnerable weakling Vladimir Putin.

There would be the risk he could take it too far. Speaking to The Telegraph earlier this year, Waters said this of his estranged Pink Floyd bandmates: “They can’t write songs, they’ve nothing to say. They are not artists! They have no ideas, not a single one between them. They never have had, and that drives them crazy.” Ergo, Waters now claims sole responsibility for 1973’s The Dark Side Of The Moon: “Let’s get rid of all this ‘we’ crap! We all contributed – but it’s my project and I wrote it. So… blah!” The songwriting credits tell a different story.

The ideas man’s latest idea has been to rerecord that classic album in full to mark its 50th anniversary. Justify that, Waters! The Dark Side Of The Moon? No one’s really nailed those songs before, have they? No, I’m not talking about the Pink Floyd original. The Flaming Lips’ 2009 version is the definitive recital. Why? For one thing, they treat the material less preciously than its original creators. Secondly, it’s got Henry Rollins on it. Case closed.

It is hardly surprising that the pandemic saw several stars seeking comfort by delving into past glories. Dark Side Redux follows The Lockdown Sessions on which Waters rerecorded six songs from his back-catalogue, mostly taken from the Pink Floyd years. It had the advantage of being far shorter than U2’s exhaustively insipid Songs Of Surrender.

Apparently Waters performed just one bass solo (on ‘Us And Them’) and a small amount of analogue synth at the beginning of his new Dark Side LP. This left his collaborators, especially producer and multi-instrumentalist Gus Seyffert, to do the heavy lifting. Waters has therefore directed most of his own efforts into the album’s added narration which is easily the worst thing about it, as most listeners – or victims – will surely agree. No doubt Waters believes these soliloquies are coming across as wise, poetic, philosophical, deep, etc. but they are utterly devoid of humour or any sense of self-awareness and always as welcome as a dung beetle in one’s cornflakes.

Matters improve only moderately when Waters stops talking and starts singing. His now-gravelly vocals rasp deeply. While this does provide some sense of gravitas or poignant frailty, they are far too dominant in the mix, cranked up to the max at the expense of every other sound. When he growls the word “Monneeeeeyyyy” with unbridled relish it’s as if Rob Brydon is competing with Steve Coogan to see who can do the most ridiculous impersonation of the late Leonard Cohen. As with the narration, the singing results in a similarly violating experience as having a stalker harass you down the telephone line (and not in a good way like ‘Through The Window’ by Prurient).

As for the music, the complete absence of lead guitar solos could be interpreted as yet another bitter dig at David Gilmour. On the plus side, this gap does provide space for some nifty replacements using elegant string arrangements, warm keyboard textures and some really quite beautiful theremin accompaniment. The weakest link being Waters’ own vocal presence, if he had left this album as an instrumental reinterpretation it could well have been a triumph. Alas, he did not. Have you ever listened to an audiobook through one device with Radio 3’s Night Tracks playing simultaneously on another? It’s not as good as that.

We don’t have to wait for The Inquisitor to get round to Waters and ask him to account for this particular project because the rarely camera shy YouTuber has already made the effort. It’s more reflective, he says, and yes the music does have a mellower and more introspective feel than the original, for what that’s worth. He also claims that “not enough people recognised what it’s about, what it was I was saying then”, so the new version is “more indicative of what the concept of the record was”.

On the Dark Side episode of the documentary series Classic Albums, Waters famously wrote off the lyrics he’d penned back then as “sort of lower sixth [form]”. They actually got worse on the albums thereafter, as his critics have emphasised: more adolescent, clunky, self-pitying and solipsistic. Go through the lyric sheets of the Pink Floyd albums on which Waters increasingly came to dominate and it’s like seeing a case study of Devo’s de-evolution theory in action.

In the moments when the barrage of freshly scribed narration makes much sense, the main message seems to be that Waters is now 80 years old and having to face the inevitable, which can’t precisely have been the case when he was making the original recording on the cusp of turning 30. So the chances are that Waters himself no longer recognises what Dark Side was really about, if anything much, or what exactly he was saying back then. The death of Waters’ father in the Second World War continues to loom large, if not very coherently what with all the dodgy metaphors and imprecise details, but perhaps that is part of the point. Once a goose-pimpling centrepiece thanks largely to Clare Torry’s soulful and wordless vocal improvisations, ‘The Great Gig In The Sky’ is now a long-winded tribute to the poet Donald Hall, who died in 2018, and his assistant Kendel Currier. That famous singing passage is recreated with an effect that might as well be someone who’s just been winded by a low-flying football moaning into a plastic cup.

Waters hammers home the point that that war and evil are, of course, BAD THINGS. As for the straightforward solution to humanity’s ongoing woes, Waters seems to think that if everyone, especially the “fucking warmongers” he targets in the liner notes, had bought and heeded The Dark Side Of The Moon the first time round, then world peace would have been achieved post-haste. That would be a useful accomplishment to have in the back pocket when The Inquisitor comes to call but life is not as simple as Waters’ post-hippie idealism conceptualises it to be. When Pink Floyd regrouped in 2005, two individuals who were said to be thrilled by the booking were Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. The Dark Side Of The Moon is David Cameron’s favourite album of all time. The latter ex-Prime Minister actually has a lot in common with Waters. Both men have taken charge of something arrogantly and made it immeasurably worse than it was in the first place. Also, each one owns a wardrobe full of inflatable pigs.

One trait that certainly hasn’t diminished with older age is Waters’ chutzpah, so admire that if you must. What with everything else that he broadcasts, blogs and blathers from the stage, this record is further evidence that Waters has simply never learned when to shut up.

Genesis – Wembley, London 1975 – 100 Greatest Bootlegs – Number 71

From 100greatestbootlegs.blogspot.com

.

The Complete BBC Radio Show GEN750415TM

(First circulated March 2009)

Sourced from the master reels, the audio quality is stunning.

“One of the most bootlegged radio broadcasts in Genesis’ history was recorded at the Empire Pool, Wembley. Genesis played two nights at Wembley and the BBC were contacted to record both nights. Some sources quote the recording date as 14th, but comparison with an audience tape from 15th shows the recording is from the second night. The proliferation of this show on bootleg is partly due to the large number of broadcasts it has received: at least three by the BBC; several world-wide broadcasts of a BC transcription LP; some King Biscuit broadcasts and numerous Westwood One airings.

The first broadcast on BBC’s “In Concert” program, 12th July 1975 at 6:30 pm, was bootlegged by the classic “Awed Man Out” (TAKRL 1975 – LP), minus ‘Watcher of the Skies’. The BBC pressed a quadrophonic LP to accompany the original broadcast, hosted by Brian Matthew and named “POP SPECTACULAR featuring Genesis In Concert”. As often happens with BBC LP’s this transcription differs from the corresponding UK broadcast: ‘In The Cage’ was added at the expense of ‘Lilywhite Lilith’ and splicing out a couple of chunks of ‘The Waiting Room’. Although an encore, ‘Watcher of the Skies’ whenever broadcast is always the first track played. Curiously the final verse of ‘In The Cage’ present on the audience recording, is edited out of the broadcasts giving the impression Peter forgot the lyrics.” (David Dunnington)

1. Watcher Of The Skies 7:45

2. Cuckoo Cocoon 2:21

3. In The Cage 6:49

4. The Grand Parade Of Lifeless Packaging 3:04

5. The Story of Rael (part 1) 1:30

6. Back In N.Y.C. 6:00

7. Hairless Heart 2:35

8. Counting Out Time 3:54

9. The Carpet Crawlers 5:43

10. Lilywhite Lilith 2:36

11. The Waiting Room 9:34

12. Anyway 3:35

13. Silent Sorrow In Empty Boats 1:13

14. The Colony Of Slippermen (part 1: Arrival) 1:53

15. Ravine 1:28

16. The Light Dies Down On Broadway 3:32

17. Riding The Scree 4:41

Still waiting for the book.