The Orb/David Gilmour Metallic Spheres (2010)

From pitchfork.com/

Over the past few years, the Orb have been nudging their sound back toward its techno-hippie roots; now they team with Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour

The Orb have never hidden their art-rock leanings. Their debut album, released in 1991, was a double-vinyl epic entitled, with a knowing nod to the bongs-and-blacklights crowd, Adventures Beyond the Ultraworld. Despite being marketed as house music, Ultraworld was really designed to flow like those spacey prog-song suites that so captivated stoned 70s kids who gorged on sci-fi novels. (The Orb just ditched the “songs” part of the suite equation.) And though the rhythms on the new Metallic Spheres occasionally recall techno and hip-hop and other more recent inventions, this albums sounds a hell of a lot like it could have been playing in a planetarium circa 1974.

Again, as much of that is due to the Orb as to special guest legend David Gilmour of Pink Floyd. The Orb’s music got chillier, tighter, and altogether less shaggy as we moved away from rave’s sloppy love-in and toward the precision-tooled club music of the 21st century. But over the past few years, Orb co-founder Alex Paterson has been gently nudging the group’s sound back toward its techno-hippie roots. Collaborating with Gilmour feels in some ways like the Orb’s coming home after a good many years spent wandering the post-rave wilderness. Their last few albums have sounded as if the band were wondering where exactly they could take their music next, while not quite sure if they truly wanted to revert to their old sound, and the master’s presence feels like it gave the disciples license to go all-out retro.

Mostly wordless, full of spaced-out sound effects, and making no concessions to good ol’ verse-chorus-verse structures, Spheres is a trip, to use a term once unabashedly uttered by Floyd devotees and revived by Orb aficionados with more of a knowing wink. A headphones record, in other words. Light show and chemical refreshment totally optional. Over two long tracks subdivided into shorter movements, Paterson and fellow Orb-er Youth thread together a post-rave library’s worth of slow-rolling chillout-room rhythms, referencing everything from dub to krautrock along the way, as Gilmour sweeps in and out on guitar, dropping little shiver-inducing melodic runs like it’s no big deal. Though his playing here meanders by design, Gilmour sounds neither lazy nor indulgent, more like a virtuoso who doesn’t want to actually seem like he’s sleepwalking through his performance. The Orb, on the other hand, are showing off in the best way possible, again crafting the lush, cosmic rhythms they were once so good at, hoping to impress a long-time hero. In the process, they also manage to impress listeners who’ve stuck with the band through some pretty ropey recent material.

Records like Spheres usually get filed as “ambient” these days, but that’s not quite right here. Sure, it’s gorgeous and hypnotic and more about beats than songs and all the things you’d probably expect from this pairing. It’s also immersive in an old-school way, a long-player of a very pre-digital vintage, a record for people with enough free time (or a long enough commute) to lose themselves in a 50ish-minute composition. With its dramatically orchestrated peaks and valleys, it’s an album designed to be listened to, to Take You Somewhere as you lay on your bedroom floor, to conjure futuristic images in the mind’s eye of folks who were once teenage fans. In that sense, it’s still not quite as successful as the Orb’s classic material, and a little too subdued, lacking both the goofy sampleadelic grandeur and the ear-grabbing pop pulse of the Ultraworld era. But it’s still the most focused and listenable Orb album in years. And hey, if you want to treat it as background music, that’ll work just fine, too.

Saucer Full Of Sour Milk: Roger Waters’ Dark Side Of The Moon Redux (2023)

From thequietus.com/

If there is one thing that ruins Roger Waters’ rerecording of Dark Side Of The Moon – Roger Waters’ Dark Side Of The Moon Redux – then it’s Roger Waters, finds JR Moores

Back in the pre-poptimism heyday of music journalism when people still cared about what kind of crap was being peddled to hapless consumers, musicians were sometimes asked to justify themselves. Interviewing stars for Smash Hits or Q magazine, the legendary Tom Hibbert (1952 – 2011) liked to, as one obituary put it, “give his subjects the impression that, despite their obvious successes, they were still somehow shameful underachievers, and then sit back quietly with a cigarette to enjoy the panicked response.

He sounds a bit like the Grub Street equivalent of The Inquisitor from the sci-fi sitcom Red Dwarf, a terrifying character that continues to haunt the ongoing existential crises of those who were unfortunate enough to watch the show’s fifth series at an impressionable age. In Episode Two, the crew of the titular spaceship encounter a droid who has survived until the end of time, discovered that there is no God or afterlife, and so the sole purpose in life is to make it worthwhile. The droid then roams eternity to visit every individual throughout history and assess each one accordingly. Those unable to justify their existence, who are deemed to have wasted their lives, are erased by The Inquisitor and replaced by other beings who never had the opportunity. “The unfertilised eggs,” as the mechanoid Kryten explains. “The sperms that never made it.”

Speaking of which, Roger Waters has spaffed out a new version of The Dark Side Of The Moon. Now there’s someone who wouldn’t break into a sweat were The Inquisitor to knock on the door of his Hamptons palace. This is the bloke who was described by writer and director Nigel Lesmoir-Gordon as having too much self-importance to appreciate the ego-diminishing experience of LSD. Waters could point The Inquisitor towards the many platinum discs lining the walls of his endless corridors. He could recall flying in the face of punk by releasing one of the most bloated albums ever made to astronomical success in 1979. He could note the joy his palatable arena prog has brought to countless baby boomers over the decades and occasionally some younger listeners. Additionally he could draw attention to his earnest global activities, such as sticking it to Israel and being one of the few voices in the West to defend the reputation of vulnerable weakling Vladimir Putin.

There would be the risk he could take it too far. Speaking to The Telegraph earlier this year, Waters said this of his estranged Pink Floyd bandmates: “They can’t write songs, they’ve nothing to say. They are not artists! They have no ideas, not a single one between them. They never have had, and that drives them crazy.” Ergo, Waters now claims sole responsibility for 1973’s The Dark Side Of The Moon: “Let’s get rid of all this ‘we’ crap! We all contributed – but it’s my project and I wrote it. So… blah!” The songwriting credits tell a different story.

The ideas man’s latest idea has been to rerecord that classic album in full to mark its 50th anniversary. Justify that, Waters! The Dark Side Of The Moon? No one’s really nailed those songs before, have they? No, I’m not talking about the Pink Floyd original. The Flaming Lips’ 2009 version is the definitive recital. Why? For one thing, they treat the material less preciously than its original creators. Secondly, it’s got Henry Rollins on it. Case closed.

It is hardly surprising that the pandemic saw several stars seeking comfort by delving into past glories. Dark Side Redux follows The Lockdown Sessions on which Waters rerecorded six songs from his back-catalogue, mostly taken from the Pink Floyd years. It had the advantage of being far shorter than U2’s exhaustively insipid Songs Of Surrender.

Apparently Waters performed just one bass solo (on ‘Us And Them’) and a small amount of analogue synth at the beginning of his new Dark Side LP. This left his collaborators, especially producer and multi-instrumentalist Gus Seyffert, to do the heavy lifting. Waters has therefore directed most of his own efforts into the album’s added narration which is easily the worst thing about it, as most listeners – or victims – will surely agree. No doubt Waters believes these soliloquies are coming across as wise, poetic, philosophical, deep, etc. but they are utterly devoid of humour or any sense of self-awareness and always as welcome as a dung beetle in one’s cornflakes.

Matters improve only moderately when Waters stops talking and starts singing. His now-gravelly vocals rasp deeply. While this does provide some sense of gravitas or poignant frailty, they are far too dominant in the mix, cranked up to the max at the expense of every other sound. When he growls the word “Monneeeeeyyyy” with unbridled relish it’s as if Rob Brydon is competing with Steve Coogan to see who can do the most ridiculous impersonation of the late Leonard Cohen. As with the narration, the singing results in a similarly violating experience as having a stalker harass you down the telephone line (and not in a good way like ‘Through The Window’ by Prurient).

As for the music, the complete absence of lead guitar solos could be interpreted as yet another bitter dig at David Gilmour. On the plus side, this gap does provide space for some nifty replacements using elegant string arrangements, warm keyboard textures and some really quite beautiful theremin accompaniment. The weakest link being Waters’ own vocal presence, if he had left this album as an instrumental reinterpretation it could well have been a triumph. Alas, he did not. Have you ever listened to an audiobook through one device with Radio 3’s Night Tracks playing simultaneously on another? It’s not as good as that.

We don’t have to wait for The Inquisitor to get round to Waters and ask him to account for this particular project because the rarely camera shy YouTuber has already made the effort. It’s more reflective, he says, and yes the music does have a mellower and more introspective feel than the original, for what that’s worth. He also claims that “not enough people recognised what it’s about, what it was I was saying then”, so the new version is “more indicative of what the concept of the record was”.

On the Dark Side episode of the documentary series Classic Albums, Waters famously wrote off the lyrics he’d penned back then as “sort of lower sixth [form]”. They actually got worse on the albums thereafter, as his critics have emphasised: more adolescent, clunky, self-pitying and solipsistic. Go through the lyric sheets of the Pink Floyd albums on which Waters increasingly came to dominate and it’s like seeing a case study of Devo’s de-evolution theory in action.

In the moments when the barrage of freshly scribed narration makes much sense, the main message seems to be that Waters is now 80 years old and having to face the inevitable, which can’t precisely have been the case when he was making the original recording on the cusp of turning 30. So the chances are that Waters himself no longer recognises what Dark Side was really about, if anything much, or what exactly he was saying back then. The death of Waters’ father in the Second World War continues to loom large, if not very coherently what with all the dodgy metaphors and imprecise details, but perhaps that is part of the point. Once a goose-pimpling centrepiece thanks largely to Clare Torry’s soulful and wordless vocal improvisations, ‘The Great Gig In The Sky’ is now a long-winded tribute to the poet Donald Hall, who died in 2018, and his assistant Kendel Currier. That famous singing passage is recreated with an effect that might as well be someone who’s just been winded by a low-flying football moaning into a plastic cup.

Waters hammers home the point that that war and evil are, of course, BAD THINGS. As for the straightforward solution to humanity’s ongoing woes, Waters seems to think that if everyone, especially the “fucking warmongers” he targets in the liner notes, had bought and heeded The Dark Side Of The Moon the first time round, then world peace would have been achieved post-haste. That would be a useful accomplishment to have in the back pocket when The Inquisitor comes to call but life is not as simple as Waters’ post-hippie idealism conceptualises it to be. When Pink Floyd regrouped in 2005, two individuals who were said to be thrilled by the booking were Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. The Dark Side Of The Moon is David Cameron’s favourite album of all time. The latter ex-Prime Minister actually has a lot in common with Waters. Both men have taken charge of something arrogantly and made it immeasurably worse than it was in the first place. Also, each one owns a wardrobe full of inflatable pigs.

One trait that certainly hasn’t diminished with older age is Waters’ chutzpah, so admire that if you must. What with everything else that he broadcasts, blogs and blathers from the stage, this record is further evidence that Waters has simply never learned when to shut up.

Pink Floyd Live at Knebworth 1990 (2021)

From brutallyhonestrockalbumreviews.wordpress.com

There are a couple of things that really bugged me about Pink Floyd’s latest release, Live at Knebworth 1990. Firstly, versions of all of these songs recorded around the same time were released on Delicate Sound of Thunder already except “The Great Gig in the Sky”, and even that was on the 2019 re-release of the album. Given that Floyd were never ones for mixing things up from night to night, how different could the versions on Live at Knebworth 1990 be? (Spoiler alert – more than I expected, actually). So I was already thinking this release was fairly superfluous. But I’m also a little peeved that when the Later Years box set came out back in 2019, all of the CDs from the set were on the hi-res version except the Knebworth CD, which was obviously held back for this release. The “let’s hold something back so we can charge people who want it additional moolah in the future” trick record companies are always pulling really sets me off. Money grubbing parasites. So I was already a little grumpy about it before I even heard this release.

There are a couple of things that really bugged me about Pink Floyd’s latest release, Live at Knebworth 1990. Firstly, versions of all of these songs recorded around the same time were released on Delicate Sound of Thunder already except “The Great Gig in the Sky”, and even that was on the 2019 re-release of the album. Given that Floyd were never ones for mixing things up from night to night, how different could the versions on Live at Knebworth 1990 be? (Spoiler alert – more than I expected, actually). So I was already thinking this release was fairly superfluous. But I’m also a little peeved that when the Later Years box set came out back in 2019, all of the CDs from the set were on the hi-res version except the Knebworth CD, which was obviously held back for this release. The “let’s hold something back so we can charge people who want it additional moolah in the future” trick record companies are always pulling really sets me off. Money grubbing parasites. So I was already a little grumpy about it before I even heard this release.

Of course, the versions in Live at Knebworth 1990 aren’t exact clones of the versions of DSoT, but are they close enough to be worth parting with any hard-earned $$$ for? To be honest, I expected Live at Knebworth to be wholly unnecessary if you have DSoT, especially if you have the 2019 re-release.I thought that you’d have to be a super-mega-hard-core-bordering-on-obsessive-compulsive Pink Floyd fan to really need this. I thought it was mostly a release for those who really really, really feel like they need every second of music Pink Floyd ever released. Was I right? Well, let me spell out the differences between these versions and the ones on DSoT for you and you can make up your own mind.

For a couple of these songs, if there are any differences, I can’t hear them. “Shine On You Crazy Diamond” sounds fantastic, obviously – I’ve always preferred David Gilmour’s vocals on the latter-day Floyd live albums to Roger Water’s studio original. Those four mournful guitar notes near the beginning of the song are played far more mournfully than was the case on the original version. Dave’s guitar playing is as reliably sharp and melodic as ever. Don’t get me wrong, this is an outstanding version of this song. And in a blind taste test, I’d never be able to tell this one from the one on DSoT (with one extremely unfortunate exception we will talk about in a minute). Same with “Wish You Were Here”- it’s a suitably marvelous version to be sure – and completely indistinguishable from the one on DSoT. Same goes for “Sorrow”, one of the better songs from the album they were touring at the time, A Momentary Lapse of Reason. It’s a marked improvement over the studio version – the intro is far more resonant, and the outro is far more effective than the fade-out on the studio version. It’s a simply smashing version – and for all I can tell is identical to the simply smashing version on DSoT. So that’s almost half the album right there, people – if you already own these songs on Delicate Sound, you don’t need ‘em on Live at Knebworth 1990.

Some songs have differences that are definitely not an improvement. I’ve noted before that with precious few exceptions saxophones ought to be banned from all rock music, and actually several Pink Floyd songs are among those precious few exceptions (“Us and Them” is the best example, but “Shine On” as well). On Delicate Sound I thought Scott Page’s sax was even more annoying than saxophones usually are, and he played with a swagger as though he thought Pink Floyd were lucky to be on stage with him. But then the sax player on Live at Knebworth, Candy Dulfer, was evidently determined to out-Scott-Page Scott Page, and upped the obnoxiousness quotient even more than her predecessor. She plays along with the riff from the outset of “Money”, a most unwelcome addition to the arrangement, and then bloviates horrendiferously on the sax solo. She does the same on “Shine On”, which is the only way you’d know the difference between the version on Delicate Sound and this one. When a saxophonist makes me long for Scott Page, you know you’ve reached a seventh-circle-of-Hell level of saxophone awfulness. I have no doubt she is a skilled musician – but certainly not a tasteful one. It does not matter how skilled a musician is at producing notes when they lack the judgment to apply that skill judiciously, and Ms. Dulfer flings saxophone notes about helter skelter with no concern for whether they fit well with the song. On the original version Dick Parry demonstrated quite compelling how a tasteful sax part could enhance “Shine On You Crazy Diamond” – Candy Dulfer instead engages in indiscriminate musical vandalism. In spite of the brilliance of the rest of the musicians, especially David Gilmour, I’m afraid I have to take a point off for musicianship. Nice going Candy.

Other differences are in fact major improvements from the DSoT versions of these songs. “The Great Gig in the Sky” does bring something special to the table, the return of Clare Torrey, whose vocal acrobatics on the studio version are most of what made the song so special in the first place. Geez, it took three vocalists to do the song on latter-day Floyd live versions, and Roger Waters uses two, but in the original Ms. Torry did it all by her lonesome, and it was spine-tingling. She acquits herself well on the version on Live at Knebworth 1990, and while it is not quite as jaw-dropping as the original owing to a few sections where she gets a tad repetitive, for my money she still sounds phenomenal. Unfortunately, if you’ve ever watched the video she didn’t fare so well through the rest of the concert. For some reason she opted to stay on stage and sing backup with the regular backup singers, who had choreographed dance moves during the songs, and while Clare Torry may have been a powerhouse hurricane-level vocalist, a dancer she was not. There is a considerable amount of second hand embarrassment to be had watching her attempt to dance next to the smooth, graceful movements of the other singers. <<Cringe>>. But for her moment in the spotlight during “Great Gig”, she really shines.

But you know, for all of my grousing, there are actually a couple of songs that almost – almost – justify the purchase of this album even if you already have DSoT. I’m not sure what got into David Gilmour, but about halfway through the set his playing developed an energy – nay, a ferocity even – quite usual for the generally cool and professional Gilmour. If you can push past the abominationable saxophone solo – keep in mind God gave us fast forward buttons for a reason – you will hear the most fiery guitar solo on “Money” of all of the many versions I’ve ever heard. Too bad it’s mired in a swamp of saxophone awfulness. “Comfortably Numb” is a fairly standard version for most of the song, with a run of the mill mind-blowing solo after that first chorus – Gilmour has never failed to play it with his customary brilliance. But when he cuts loose soloing after the last chorus, his playing is a marvel to behold. The finest guitar solo outro for “Comfortably Numb” I have ever heard, and I’ve never heard a bad version.

But Gilmour is at his boldest and most forceful on “Run Like Hell” – I went back and listened to the version on DSoT to be sure, and there is no question, Gimour’s energetic vocals and blazing guitar kick the song up another level. The song fairly explodes out of your speakers at the finale, and I have to confess the DSoT version, great as it is, isn’t in the same league.

So is Live at Knebworth superfluous for someone who has Delicate Sound of Thunder? Well, truthfully, it is for a couple of songs. “Wish You Were Here” and “Sorrow” differ not at all, and “Shine On You Crazy Diamond” differs only in the somehow-even-more-obnoxious-than-Scott-Page saxophone. That same saxophone tragically mars a versions of “Money” that otherwise has an exceptionally powerful David Gilmour solo. But if you respect Gilmour’s playing as much as I do, you really need to hear his guitar solos on “Money”, “Comfortably Numb”, and “Run Like Hell”, which also boasts a remarkably powerful Gilmour vocal.

Indeed , while I am surprised to say it, an unusually powerful performance by Gilmour makes this release worth your time in spite of the redundancies with Delicate Sound of Thunder. And I must confess, after actually hearing Live at Knebworth 1990, I actually feel considerably less grumpy about it.

Pink Floyd Delicate Sound of Thunder (1988) expanded (2020)

From somethingelsereviews.com

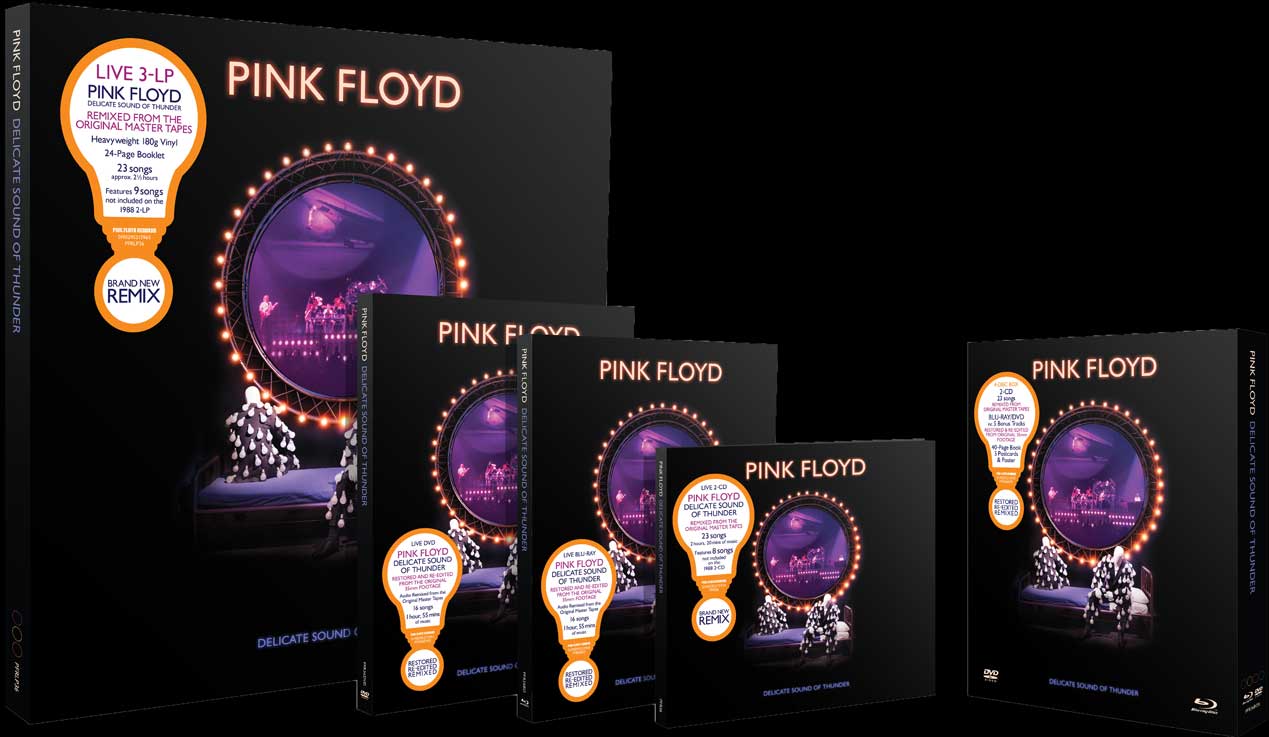

Pink Floyd continues to release reissue projects from different periods of the group’s past. An upgrade of the original Delicate Sound of Thunder serves as a follow-up to 2019’s The Later Years box, as the double live album from 1988 returns in several formats – including a three-album vinyl set, a two-CD edition, Blu-ray and DVD formats, as well as a four-disc box that includes two CDs, a DVD and a Blu-ray.

Pink Floyd continues to release reissue projects from different periods of the group’s past. An upgrade of the original Delicate Sound of Thunder serves as a follow-up to 2019’s The Later Years box, as the double live album from 1988 returns in several formats – including a three-album vinyl set, a two-CD edition, Blu-ray and DVD formats, as well as a four-disc box that includes two CDs, a DVD and a Blu-ray.

The DVD and Blu-ray in the four-disc box features five additional performances more than the 16, not previously available on the Later Years box, or standalone DVD, or Blu-ray. Along with the four-disc box, the vinyl set is what most Pink Floyd fans will want to have – even if they have the Later Years box, as it only included two seven-inch vinyl singles.

The vinyl edition of Delicate Sound of Thunder features nine additional performances not included on the original double album. This 23-track count is the same as the new double-CD set. Additionally, the three-album set is packaged in a slip case, includes a 24-page booklet and the albums are housed in poly-lined sleeves in individual album jackets. The albums are pressed on 180-gram vinyl and the tracks were remixed from the original master tapes.

Pink Floyd’s performances were taken from five August 1988 shows at the Nassau Coliseum in New York, on the heels of the release of 1987’s A Momentary Lapse of Reason – their first album after the departure of Roger Waters. The core group of David Gilmour, Nick Mason and Richard Wright was joined by Jon Carin, Tim Renwick, Guy Pratt, Gary Wallis and Scott Page, with Margret Taylor, Rachel Fury and Durga McBroom on backing vocals.

Delicate Sound of Thunder kicks off with “Shine On You Crazy Diamond, Parts 1-5” and then for the rest of the first album and Side A of the second album, there are 10 songs from Momentary Lapse of Reason. After the only song that dates to Pink Floyd’s early career, “One of These Days” from Meddle, the rest of the set features music from Dark Side of the Moon, Wish You Were Here, The Wall, and then one more song from A Momentary Lapse of Reason. There are no songs from Animals or The Final Cut.

Not only are there additional performances included on this reissue, but several tracks – “Sorrow,” “On the Turning Away,” “Comfortably Numb,” “Dogs of War,” “Another Brick in the Wall, (Part Two),” “Us and Them,” “Run Like Hell” and “Time” – feature unedited versions available now for the first time on vinyl. Occasional editing has been done to remove an ’80s-era musical gloss that sometimes marred the original performances, notably on “Money” and “Learning to Fly.”

Hearing these tracks in their remixed and in some cases dramatically changed ways, straight through on all three vinyl discs, is about the best official live album Pink Floyd audio experience – outside of the rare Pulse four-LP analog vinyl set.

Delicate Sound of Thunder is, in fact, one of only three official stand-alone live Pink Floyd albums. Pulse was released in 1995 as a four-LP or two-CD set from the tour to support The Division Bell, another post-Roger Waters project. The third is Is There Anybody Out There? The Wall Live 1980–81, released on CD in 2000. Prior to that, one disc of the 1969 double-album Ummagumma contained live material.

Neither Is There Anybody Out There? nor Pink Floyd: Live at Pompeii – originally issued in 1972 on film with a subsequent releases on DVD in 2000 and on compact disc in 2016 as part of The Early Years box – has been reissued on vinyl. Pink Floyd fans, I’m sure, would love to have all of this concert material on their turntables in the future.

There is also a wide assortment of live material from many periods in Pink Floyd’s career to draw from on the Early Years and Later Years sets that would make for excellent vinyl releases. Who knows what else lurks in the vast Pink Floyd archives? Releasing the new mix of A Momentary Lapse of Reason would be the most obvious next vinyl project that fans would love to see.

Pink Floyd Pulse (1995)

From brutallyhonestrockalbumreviews.wordpress.com

Does the concept of a “Desert Island” album even make sense anymore in 2020? (Of course, in 2020 there are a ton of things that don’t make sense anymore). Back in the day, music aficionados loved to talk about which album they would pick if they were stranded on a desert island and could only pick one album to have with them (along with some kind of magical record player that doesn’t run on electricity I guess). I mean, these days I carry my FLAC player in my pocket everywhere I go with a 400GB Micro SD card with almost 250 albums in 24 bit audio – if I can have an album on a desert island, why can’t I have my FLAC player? It’s even smaller than an lp, fits in my pocket, and doesn’t require a magical record player. We music lovers really are quite spoiled in 2020.

Does the concept of a “Desert Island” album even make sense anymore in 2020? (Of course, in 2020 there are a ton of things that don’t make sense anymore). Back in the day, music aficionados loved to talk about which album they would pick if they were stranded on a desert island and could only pick one album to have with them (along with some kind of magical record player that doesn’t run on electricity I guess). I mean, these days I carry my FLAC player in my pocket everywhere I go with a 400GB Micro SD card with almost 250 albums in 24 bit audio – if I can have an album on a desert island, why can’t I have my FLAC player? It’s even smaller than an lp, fits in my pocket, and doesn’t require a magical record player. We music lovers really are quite spoiled in 2020.

But let’s set that all aside and play the hypothetical “Desert Island” album game. Pink Floyd’s Pulse is not my #1 “Desert Island” Album – that would be The Beatles’ 1967-1970 (Blue Album) (which, oddly enough, isn’t even on my 400GB Micro SD card with almost 250 albums in 24 bit audio). Not only is 1967-1970 (Blue Album) my “Desert Island” album, it’s my “Destruction of Planet Earth” album – if the planet was facing imminent destruction and we could only save one cultural artifact to demonstrate to any alien visitors who might someday be poking through the wreckage of our planet that human existence had not been completely in vain, the Blue Album would be my choice hands down. Nothing else would even be close. Of course, I would want it carefully wrapped in Van Gogh’s Starry Night to try and save that also. Upon listening to the Blue Album these strange, alien visitors of the future would weep uncontrollably at the sheer inexpressible beauty had been lost at the destruction of planet Earth. Although if they knew what went down on Earth in the U.S. in 2020, they might find it substantially less tragic, and might instead just be more appalled at the rampant stupidity that abounded in that corner of the globe at the time. “No wonder those idiots didn’t survive” they would probably say to themselves. Those of us in the U.S. live in incredibly stupid times in 2020. But, hey, at least we have high capacity SD cards that can hold hundreds of albums in HD audio.

Pulse wouldn’t even be my second “Desert Island” choice – that would be Led Zeppelin’s The Song Remains the Same. I sense the wrinkling of noses in disgust among hard core Zeppelin fans – I know some of the really hard core ones are mumbling things like “are you kidding me? The audience recording of the Bath 1970 show totally blows it away – or it would if you could hear what was going on anyway!” Among the initiated, the 1973 Madison Square Concerts have generally been pooh poohed, but I’ve always thought TSRTS gets a bum rap. Hard core Zep fans who have lots of bootlegs like to try and make it sound like the show was just average, but I beg to differ. Sure, it takes Robert Plant a while to warm his voice up, and I’m not sure I can honestly say I’ve ever listened to “Moby Dick” live all the way through, but the fact of the matter is Page had peaked as a guitarist in the European tour a few months earlier, and was still riding high. He sounds amazing – with a mere handful of exceptions, for the last time in his career really. And once Plant gets going his vocals are as powerful as ever. John Paul Jones is his solid reliable self, and Bonzo is shaking the world as always – for their decade plus run they never really had to worry about the rhythm section, it was Page and Plant who got iffy in their later years. But not on TSRTS. “Celebration Day” kicks the crap out of the studio version. “No Quarter” has a menace sadly lacking in the Houses of the Holy version. The album has hands down the best live version of “Stairway to Heaven” on the market. And I simply can’t live without that live “The Song Remains the Same” / “The Rain Song” song cycle, my favorite tracks from any concert album ever. So yes, I am serious, you can sniff disdainfully at me all you want, but it’s my “Desert Island” list and I’m picking TSRTS as my number two.

But my number three pick goes to Pink Floyd’s Pulse. And now I’m bracing for the disdain from the hard core Pink Floyd fans: “It isn’t even really Pink Floyd without Roger Waters. It’s just a David Gilmour led Pink Floyd cover band. Man, any random show from the Animals tour kicks its butt”. No, no, and no. Pink Floyd didn’t stop being Pink Floyd when Roger Waters stormed out any more than it stopped being Pink Floyd when Syd Barrett flamed out. As for the cover band accusation that gets bandied about from time to time, sure, the Floyd had tons of extra musicians when they toured The Division Bell, but that doesn’t mean they stopped being the Floyd, and with three original members I hardly think the cover band criticism sticks. And sorry, the Animals shows were actually kind of boring. So there.

I was so excited to get the album when it came out back in 1995, but at the time I was a poor, newly married college student with a baby on the way, and I couldn’t even really afford the $21.99 it was on sale for at Circuit City. I’ll never forget coming home from work one night after it came out, walking in the bedroom and finding it on the bed, seeing that blinking red LED light on the spine. My wife had bought it for me as a surprise. And we’ve been together ever since.

I think Pulse is fantastic. I’ve been listening to it for 25 years now, I never get tired of it, I listen to at least a song or two from the album at least every few weeks. It’s one of my go-to albums when I can’t decide what I want to listen to. I may not always be in the mood for Elvis or the Beach Boys or even Zep, but I am always in the mood for Pulse. It’s a frequent companion of mine. But while I love the album, I’m not ignorant of its flaws, so let’s get them out of the way so I can talk about why I love the album so much.

And the first problem I’m gonna talk about is a pretty big one – Dark Side of the Moon. It’s cool to have a live version of a performance of the entire album, but of course it’s gonna be inferior to the studio version. Not only was Dark Side an outstanding collection of great dance songs, but the album is a sonic marvel. After almost 50 years on it still sounds pristine. Part of what makes listening to it such a marvel is that it was hands down the best engineered album of the decade. Pulse does a fair job of reproducing the arrangements from the original album, but there was no way they were ever going to reproduce the astounding sonics of the original album live on stage. Pulse is a great sounding album, no doubt – at the time it had a reputation for being one of the best recorded live albums ever. But the live version of Dark Side was never going to be the aural feast for the ears the original studio version was, there was just no way they were ever going to reproduce that sound onstage in a giant stadium.

Though not all of the versions of Dark Side songs on Pulse are necessarily inferior – the extended version of “Speak to Me” is pretty effective, what with all the crowd noise in the context of a live performance of the album, and it’s longer, with a lot more sonic treats than the original, more sound effects and synthesizer whirs and more “I’ve been mad for f****** years” and whatnot, I like it better than the original. I’ve never cared for “Any Colour You Like” on Dark Side, but the version on Pulse I find more engaging for some reason – it doesn’t sound as sterile as the original, it breathes a little better, it’s more colourful. And while the live version of “Us and Them” isn’t as good as the original, this version is fantastic in its own right. The same is true of “On the Run” – I certainly wouldn’t say it’s better than the original, but it’s a great version. The live version of Dark Side on Pulse is not without its merits.

But some songs do fall sort – the worst offender in my book is “Time”. The solo of the original version was a masterpiece of nihilism – it’s like David Gilmour channeled all of the universal despair at the cosmic insignificance and pointlessness of our existence and funneled it into his guitar solo. It questions our reasons for existing better than any mere words ever could. But on Pulse the solo is rather superficial, tossed off, and gimmicky – he throws in a few new little tricks that spoil the whole mood of the solo. And besides, overall the song loses much of its angsty pathos when performed live, especially when Richard Wright sounds all out of breath on his “Every year is getting shorter” section.

You’ve got three – count ‘em, three – great vocalists on “The Great Gig in the Sky”, but none of them is Clare Torry , and while they all do a spectacular job really, none of them surpasses the original (by the way, anybody ever see her performance with the band at Knebworth in 1990? She sounds OK on “Great Gig”, but there’s a cringey second hand embarrassment to watching her try to dance along with the other backup singers. She was a fantastic vocalist, but a dancer she was not). The band sounds pretty worn out by the time they get to “Brain Damage” and “Eclipse” – they were all in their fifties by that point, I guess you can’t expect them to maintain the energy level they had when they were much younger men, and these two songs sound pretty lifeless. The turgid version of “Eclipse” means the live version of Dark Side ends with more of a whimper than a bang, which is a shame given the electrifying ending on the original album. The songs are still the amazing songs they’ve always been, but the performances in the live Dark Side of the Moon segment of Pulse aren’t as strong for the most part as on the studio versions.

There are a few other nitpicks about the album. I’m not sure why they wanted to perform “Keep Talking” live, other than Dave’s talk box is kinda cool. But it’s a boring song that doesn’t have a lot to say: “I think I will speak now…I can’t seem to think straight…we’re going nowhere…this song’s going nowhere”. If I were Stephen Hawking, I’d be pissed Pink Floyd didn’t put me in a better song. I’m not sure why they didn’t swap that track out for the live version of “Take It Back” that’s on the DVD – I guess they figured if they had, all the good songs on The Division Bell would be on Pulse and no one would ever need to buy that album again. Also, the version of “Another Brick in the Wall” lacks any energy or spark, except Gilmour’s solo outro, the rest sounds like the band is kind of bored with the song and a little annoyed that they had to play it. No live version of “Comfortably Numb” is ever going to stack up to the original with phony sounding keyboards replacing the orchestra on the studio version, no matter how brilliantly Gilmour plays that iconic solo. And my final nitpick is that there are a couple of places where the screams on original songs are replaced quite ineffectively by the female background singers hitting a high note – specifically at the beginning to “Another Brick in the Wall” and in the “OK, just a little pinprick/there’ll be no more…” section of “Comfortably Numb” – ruins the impact in both places.

But now that we’ve got that out of the way, let’s talk about all of the reasons that Pulse is one of my very favorite albums ever:

- Has there ever been a more amazing tracklist on a live album? Sure, every Floyd fan can pick a favorite deep cut that isn’t on it, but I’d argue if you were going to assemble a Pink Floyd live album with all of the songs 90% of Pink Floyd fans could come to consensus are absolute must haves to be included on the tracklist, this album has them. Perhaps excepting “Echoes”, but other than that it has all the biggies. This is the Pink Floyd catalog boiled down to its most essential components. Would I have liked to have “Mother” or “Fearless” or “Sheep” on the album – sure, but as much as I love those songs I have to recognize that most of the tracks on the album deserve their place before they do. The tracklist really is unbeatable. And I know what some of you are thinking, how can I possible say that with so many songs from The Division Bell on the album? Well, that’s a nice segue actually, it leads me to my next point…

- Pulse redeems some songs on The Division Bell that are actually pretty classic. The Division Bell was not a great album no matter how you look at it. But it had some incredible highlights, all of which are performed in far superior versions on Pulse. Pulse would be a great album had it done nothing more than allowed the best songs on The Division Bell to reach their full potential. “What Do You Want From Me” demonstrates this three tracks in – a song that was stiff and dull and boring really comes to life in a live context – but then given the subject matter of the song it makes sense really, it is in its natural setting on Pulse. The guitar intro for “Coming Back to Life” is genuinely moving in a way the studio version isn’t, the live version sounds so much more fresh and engaging. It’s got a great message too: “ I knew the moment had arrived/For killing the past and coming back to life”. “A Great Day for Freedom” intertwines the messy end of the Iron Curtain with the messy end of a personal relationship, and it’s a parallel that works – and works so much better in the live version. And the live version of “High Hopes” is so much more expansive and majestic than the Division Bell version. Only “Keep Talking” fails to improve in the live version, but there’s not much you can do to improve a song that lame. It’s almost like these songs needed a connection with a live audience to bring out their potential, and I can’t bring myself to listen to the studio versions of them anymore because the Pulse versions are so much better. But you know, it isn’t just the songs from The Division Bell on Pulse that are better than the originals…

- I know this is heresy, but even some of the classic Floyd songs have versions on Pulse that are better than the originals. Now I am well aware that I am stepping into some really controversial territory here, but I’m just gonna say it – the Pulse version of “Shine On You Crazy Diamond” kicks the crap out of the studio original. For a couple of eminently defensible reasons. First and foremost, I’ve always thought those four guitar notes at the beginning of the song were too rushed and unemotional in the studio version – on Pulse those notes are given time to emote, they are far more melancholy and sad, they convey far better the emotion of the song. It’s a little thing, sure, but for me it really sets the tone for the rest of the song. Dave’s guitar playing at the beginning of the song is far more evocative on Pulse than on Wish You Were Here. Also, this is the only version (other than on the 2001 compilation Echoes: The Best of Pink Floyd) where you have all of the vocals sections in one place – on Wish You Were Here the last verse is stranded clear at the end of the album away from the rest, and it isn’t there at all for the version on Delicate Sound of Thunder. Finally, while there is something to be said for Roger Water’s manic vocals on the studio version given the song is about Syd Barrett going ‘round the bend, personally I think David Gilmour just sings it better. I think this is the best version of the song, hands down.

Similarly, I think Pulse has the best version ever of “Astronomy Domine”. Sure, it isn’t as hippy trippy psychedelic as the original or the live version on Ummagumma, but I love the firepower of the high-octane version on Pulse. It has so much energy and spunk. This live version is to the original as riding a bullet bike is to huffing paint in your parent’s basement, it’s like riding a roller coaster vs. sitting around watching Youtube videos – I’ll take the thrill and excitement of the Pulse version over the stoned ambiance of the original any day. It’s exciting, and kicks into interstellar overdrive in the instrumental section in the middle – what a ride!

Finally – and I know I am going to lose a lot of you on this one too – “Run Like Hell” is way better on Pulse than the version on The Wall. Don’t get me wrong, I miss Roger Water’s almost-out-of-control vocals, but Guy Pratt does a good enough job that I hardly miss him, and it just has so much more muscle than the studio version. The original sounds pretty anemic next to it, if you ask me. It’s an arena-sized song that probably needs an arena to reach its full potential.

Even those classic Pink Floyd songs that aren’t better in their Pulse versions are still pretty good – there’s a great version of “Hey You”. “Comfortably Numb” is still great even with synths replacing the strings, and David Gilmour’s solo at the end is predictably fantastic. And I don’t mind the audience sing-along to “Wish You Were Here” – in the context of a live concert, it works for me. I enjoy listening to all of them, even if the originals are better, I have no real gripes with them. And you do get the best ever versions of A Momentary Lapse of Reason leftovers “Learning to Fly” and “Sorrow”. I know a lot of people hate it, but I’ve always liked “Learning to Fly”, and this version is more alive than the studio original, and played more sharply than the version on Delicate Sound of Thunder. Love the percussion on this one, its pretty cool. Likewise, the intro to “Sorrow” is far more interesting and carries more emotional heft than any version that preceded it, and the end of the live version is far superior to the fade out on the studio original. The only song on the whole album I don’t really like listening to is “Keep Talking”, and as I said earlier, there was no salvaging that one no matter what they did.

- David Gilmour is a guitar god, and listening to him play live is a religious experience. I lucked out when Gilmour toured back in 2016, I had a business trip to Chicago that happened to coincide with one of his shows there. The guy is amazing – he isn’t the fastest guitarist, but he is certainly the most melodic, and has a better ear for tone than just about anybody. Seeing Roger Waters live is a blast, but seeing David Gilmour live is transcendent. And as you would expect, his playing on Pulse is spectacular. His voice is a little rough – that is the only area where Delicate Sound of Thunder is better than Pulse, his voice is a lot smoother on DSoT, mostly because Pulse was recorded in the latter end of a worldwide tour when his voice had been through a lot of shows already. Sometimes it gives his vocals a grit that enhances the song – and never is his voice so rough that it detracts from the experience any. In every other way, Pulse is the far better live album of the two – the band is more confident, the arrangements are better fleshed out, the track selection is better, with the sole exception of “On the Turning Away” all the great songs from on Delicate Sound of Thunder are also on Pulse in superior versions (that is, so long as you are listening to a version of Pulse with “One of These Days” – the best version that has the track is the 2016 Bernie Grundman vinyl remaster. Outstanding sound quality on that one).

- Unlike every single other live album from that era, it doesn’t sound over-processed. While not Dark Side of the Moon caliber sonics, the album really does sound great. Beginning in the late 80s and on through the 90s live albums had this weird thing where everything was over-processed – the guitars hardly sound like guitars on a lot of them, I can hardly listen to live albums from that era. Take a listen to George Harrison’s Live in Japan as one of the worst offenders, but hardly the only one. You don’t get that on Pulse, which is odd given how synthesizer-heavy the album is, you’d think overprocessing would be an easy trap for them to fall into with all the technology they were using all over the place. But then David Gilmour has always been the greatest practitioner of exemplary guitar tech, he always sounds great, I don’t know who his guitar tech is, but the guy is amazing. Given all the sounds effects and tapes loops and everything, the album sounds surprisingly organic. Too many live albums of the time sounded so plastic, its hard to hear the musicianship under all the layers of audio processing – not this one.

- You gotta admit, that blinking light on the spine of the CD case is pretty cool. I tell you, in this day of digital downloads music has become more accessible, more portable, and easier to listen to, but you can’t put a blinking LED light on a digital download. You young ‘uns are missing out.

I listen to Pulse more than I listen to any other Pink Floyd album. Maybe that means I’m not one of the cool kids, the ones who think Ummagumma is the only real live Floyd album, but other than possibly Dark Side it has more bang for the buck than any other Pink Floyd album. I know I’ve just shot any chance of having a reputation for being brutally honest all to hell with this review, but I can’t help it. I love Pulse, and I always will.

Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon (1973): 10 Things You Didn’t Know

From rollingstone.com March 2018

Paul McCartney’s scrapped cameo, a Silver Surfer cover concept and other factors that played into the band’s 1973 psychedelic masterpiece

There are hit albums, and then there’s Dark Side of the Moon. Pink Floyd‘s eternally popular song cycle has sold more than 15 million copies in the U.S. since its release on March 1st, 1973, and more than 45 million units worldwide. A true colossus of classic rock, the album made its creators — bassist/vocalist Roger Waters, guitarist/vocalist David Gilmour, keyboardist/vocalist Rick Wright, and drummer Nick Mason — incredibly wealthy, and ultimately spent a mind-boggling 937 weeks on the Billboard 200.

There are hit albums, and then there’s Dark Side of the Moon. Pink Floyd‘s eternally popular song cycle has sold more than 15 million copies in the U.S. since its release on March 1st, 1973, and more than 45 million units worldwide. A true colossus of classic rock, the album made its creators — bassist/vocalist Roger Waters, guitarist/vocalist David Gilmour, keyboardist/vocalist Rick Wright, and drummer Nick Mason — incredibly wealthy, and ultimately spent a mind-boggling 937 weeks on the Billboard 200.

In addition to its massive commercial success, Dark Side of the Moon was also a career-defining artistic achievement for the British quartet, one which marked Pink Floyd’s transition from an experimental, jam-oriented progressive outfit primarily beloved by college students and assorted “heads,” to a top-echelon rock act characterized by its rich songwriting – as well as by Waters’ mordant worldview. Recorded at London’s Abbey Road Studios in various sessions from May 1972 through January 1973, the album’s cerebral soundscapes (exquisitely captured on tape by Abbey Road engineer Alan Parsons, and mixed with the help of veteran producer Chris Thomas) and heavy lyrical musings on the human condition inspired countless bong-fueled headphone listening sessions in darkened bedrooms, but its songs also sounded great on FM (and even AM) radio.

And, perhaps most crucially, the record had genuine meaning. Originally conceived by the band as a cohesive collection of songs about the pressures of life as a musician, Dark Side of the Moon eventually expanded to include songs about broader topics such as wealth (“Money”), armed conflict (“Us and Them”), madness (“Brain Damage”), squandered existences (“Time”) and death (“The Great Gig in the Sky”). As Waters told Rolling Stone in 2011, “Dark Side was the first [Pink Floyd album] that was genuinely thematic and genuinely about something.” And as artists like Radiohead and Flaming Lips (both of whom have been profoundly influenced by Dark Side) can attest, the album’s music and lyrics still hold up beautifully today.

Here are 10 things you might not know about Dark Side of the Moon.

1. Dark Side of the Moon was the first Pink Floyd album to feature Roger Waters as its sole lyricist.

Roger Waters had been contributing lyrics to Pink Floyd albums since 1968’s A Saucerful of Secrets (he also received co-writing credit on the instrumentals “Pow R. Toc H.” and “Interstellar Overdrive” from The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, the band’s 1967 debut), but Dark Side marked the first — though definitely not the last — time that the bassist took the lyrical reins for an entire Floyd LP. Along with adhering to a cohesive concept, Waters wanted Dark Side to feature lyrics that were more lucid and direct than anything the band had written before.

“That was always my big fight in Pink Floyd,” Waters is quoted as saying in Mark Blake’s Comfortably Numb – The Inside Story of Pink Floyd. “To try and drag it kicking and screaming back from the borders of space, from the whimsy that Syd [Barrett, the band’s original leader, who had written the bulk of the material on Piper] was into, to my concerns, which were much more political and philosophical.”

Though Waters’ lyrical dominance on Dark Side essentially planted the seeds for the massive rift that would eventually occur between him and the rest of the band, it was actually welcomed at the time. “I never rated myself terribly highly in the lyrics department, and Roger wanted to do it,” Gilmour admitted to Rolling Stone in 2011. “I think it was a sense of relief that he was willing to do that. At the same time, him being the lyricist and more of the driving force didn’t ever mean that he ought to be in full charge of the direction on the musical side of things. So we’ve always had a little bit of tension in those areas.”

2. The album was very nearly called Eclipse.

From the beginning, the band had intended to call their new album Dark Side of the Moon — a reference to lunacy, as opposed to outer space — but when British heavy blues rockers Medicine Head released an album of the same name in 1972, it caused the Floyd to rechristen their project as Eclipse. “We weren’t annoyed at Medicine Head,” Gilmour told Sounds magazine. “We were annoyed because we had already thought of the title before the Medicine Head album came out.” But when the Medicine Head album stiffed and quickly sank into obscurity, Pink Floyd felt free to revert back to their album’s original title.

3. Floyd fans were first treated to Dark Side of the Moon in concert more than a year before the album was actually released.

Though the lush textures and spacious arrangements of Dark Side of the Moon make it sound like a purely “studio” project, the band actually aired out all of the songs in concert — in the exact same sequence that they would appear on the album — more than a year before the album’s official release. The band premiered Dark Side of the Moon: A Piece for Assorted Lunatics (as it was provisionally known at the time) at the Brighton Dome on January 20th, 1972; and though it was inadvertently cut short that night by what Waters called “severe mechanical and electric horror,” the band went on to perform the song cycle in its entirety in during the rest of their 1972 live dates, further refining the songs (and the transitions between them) as they went. The band would eventually record all 10 of the album’s songs onto the same reel of 16-track master tape at Abbey Road, an unusual approach that nonetheless paid considerable artistic dividends.

“The way one track flowed into another was an extremely important part of the overall feel,” Alan Parsons told Rolling Stone in 2011. “So we could work on the transitions as part of the recording process rather than just part of the mixing process.”

4. The original live arrangement of “On the Run” bore little resemblance to the electronic freakout on the record.

Of all the Dark Side songs played live by the band in 1972, “On the Run” was the one that was most radically transformed in the studio. Originally known as “The Travel Sequence,” the instrumental was originally a guitar-driven jam — but it received a massive electronic makeover in the studio, thanks to a portable modular analog synthesizer known as the EMS Synthi AKS. The synth, which featured a built-in keyboard and sequencer contained in a suitcase (appropriately ironic, since the piece was originally inspired by Wright’s fear of flying), was also used on the album’s “Any Colour You Like.” “There were endless, interesting possibilities for that little device,” Gilmour told Rolling Stone. “We’d always considered ourselves as being a bit electronic. I always had an obsession with finding sounds that would turn something into 3D.”

5. “Money” was influenced by Booker T and the MGs.

Pink Floyd’s first Top 20 hit in the U.S. (it reached Number 13 on the Billboard Hot 100 in July 1973), “Money” is Dark Side‘s most aggressively rocking track. With its tricky 7/4 time signature (except for during the guitar-solo segment, when the song switches to 4/4), Waters’ indelible bass riff, Gilmour’s wailing guitar lead, a squalling solo from saxophonist Dick Parry, and a distinctive sound collage loop made up of ringing cash registers and rattling coins, the recording all but obscures its roots in the Memphis R&B of Booker T and the MGs — but they’re definitely in there, according to Gilmour.

“Getting specific about how and what influenced what is always difficult,” he told Rolling Stone in 2003, “but I was a big Booker T fan. I had the Green Onions album when I was a teenager. And in my previous band, we were going for two or three years, and we went through Beatles and Beach Boys, on to all the Stax and soul stuff. We played ‘Green Onions’ onstage. I’d done a fair bit of that stuff; it was something I thought we could incorporate into our sound without anyone spotting where the influence had come from. And to me, it worked. Nice white English architecture students getting funky is a bit of an odd thought … and isn’t as funky as all that [laughs].

6. Paul McCartney’s contributions to the album were deleted – but the Beatles made a surprise appearance on the record.

In an attempt to further tie Dark Side‘s songs together, Roger Waters came up with the idea of recording interviews with Abbey Road staffers, road crew members, and anyone else working at the studio — asking them a series of questions about subjects ranging from the banal (favorite colors and foods) to the deeply serious (madness and death) — and then threading some of the interview snippets into the final mix. Paul McCartney, who was finishing Wings’ Red Rose Speedway album at Abbey Road, was actually among the interviewees, but Waters deemed his answers unusable. “He was the only person who found it necessary to perform, which was useless, of course,” Waters told Pink Floyd biographer John Harris. “I thought it was really interesting that he would do that. He was trying to be funny, which wasn’t what we wanted at all.”

Even so, McCartney — or at least his music — still managed to make a brief appearance on the album. If you listen close to the end of “Eclipse,” the album’s closing track, a passage from an orchestral version of the Beatles’ “Ticket to Ride” can be heard; the song was apparently playing in the background at the studio while Abbey Road doorman Gerry O’Driscoll (who delivered the immortal lines, “There is no dark side of the moon, really. Matter of fact, it’s all dark. The only thing that makes it look light is the sun.”) was being recorded.

7. “Us and Them” was a reject from the Zabriskie Point soundtrack.

The second of two singles released from Dark Side (“Money” was the first) and a minor hit in the U.S. and Canada, “Us and Them” began life in 1969 as a lovely piano-and-bass instrumental called “The Violent Sequence,” which as written by Wright and Waters and submitted for inclusion in the soundtrack of Michelangelo Antonioni’s counterculture drama Zabriskie Point. While the Italian director would eventually include three Pink Floyd recordings — “Heart Beat, Pig Meat,” “Crumbling Land” and “Come in Number 51, Your Time Is Up” — on the soundtrack, he didn’t feel that “The Violent Sequence” was appropriate for the film. In an interview for Classic Albums: The Making of Dark Side of the Moon, Waters recalled Antonioni saying, “It’s beautiful, but too sad. It makes me think of church!” More than two years after it was initially rejected by Antonioni, the band revisited the demo and recast it as a moving meditation on war and poverty.

8. An image of the Silver Surfer was originally considered for the album’s cover.

With its evocative, eye-catching graphic of a prism turning light into color, Dark Side of the Moon‘s album cover — created by English graphic designer George Hardie with input from Storm Thorgerson and Aubrey Powell of Hipgnosis – is one of the most iconic designs to ever grace an LP. “When Storm showed us all the ideas, with that one, there was no doubt,” Gilmour recalled to Rolling Stone in 2003. “It was, ‘That is it.’ It’s a brilliant cover. One can look at it after that first moment of brilliance and think, ‘Well, it’s a very commercial idea: It’s very stark and simple; it’ll look good great in shop windows.’ It wasn’t a vague picture of four lads bouncing in the countryside. That fact wasn’t lost on us.”

So it’s interesting to imagine the album with an entirely different cover — specifically, the one suggested by Hipgnosis that would have featured an image based on the comic book character the Silver Surfer. “We were all into Marvel Comics, and the Silver Surfer seemed to be another fantastic singular image,” Powell recalled in an interview with John Harris. “We never would have got permission to use it. But we liked the image of a silver man, on a silver surfboard, scooting across the universe. It had mystical, mythical properties. Very cosmic, man!”

9. Dark Side of the Moon was the first Pink Floyd album to break into the US Top 40.

Given Dark Side‘s multi-platinum sales figures, and the impressive Stateside success of Pink Floyd’s subsequent studio albums, it’s easy to forget that the band’s first seven LPs all fared pretty poorly in the United States; before Dark Side, the band’s biggest U.S. hit had been Obscured by Clouds, their soundtrack for the French film La Vallée, which peaked at Number 46 on the Billboard 200 in the summer of 1972. But thanks to a massive promotional push by Capitol Records, and regular spins of “Money” by American radio DJs, Dark Side of the Moon rose all the way to the top of the Billboard 200 within two months of its release.

“It went up the American charts quite quickly,” Waters recalled to Rolling Stone in 2003. “We were on tour in the States while that was happening. It was obviously going to be a big record — particularly after AM as well as FM radio embraced ‘Money.’”

10. Proceeds from the album helped fund Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

As if Dark Side of the Moon wasn’t enough of a pop cultural landmark in itself, the album’s success was also partly responsible for the existence of the brilliantly absurd 1975 film comedy Monty Python and the Holy Grail. The members of Pink Floyd often spent their downtime during the Dark Side sessions watching Monty Python’s Flying Circus on BBC2, so when the British comedy troupe ran into difficulty raising money for their first full-length feature film, the Floyd — now flush with cash from the sales of Dark Side — were more than happy to pony up 10 percent of the film’s initial £200,000 budget.

“There was no studio interference because there was no studio; none of them would give us any money,” Holy Grail director Terry Gilliam recalled in a 2002 interview with The Guardian. “This was at the time [British] income tax was running as high as 90 percent, so we turned to rock stars for finance. Elton John, Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, they all had money, they knew our work and we seemed a good tax write-off. Except, of course, we weren’t. It was like The Producers.”

Pink Floyd Wish You Were Here (1975): Pink Floyd’s Seminal ode to the tragic life of Syd Barrett

The iconic cover art for Pink Floyd’s seminal 1975 album Wish You Were Here speaks volumes. It depicts two suited men shaking hands, one of whom is engulfed in flames. What is so absorbing, however, isn’t the fact that one of the figures is on fire, but that he doesn’t seem to care he’s on fire.

The iconic cover art for Pink Floyd’s seminal 1975 album Wish You Were Here speaks volumes. It depicts two suited men shaking hands, one of whom is engulfed in flames. What is so absorbing, however, isn’t the fact that one of the figures is on fire, but that he doesn’t seem to care he’s on fire.

The image is perhaps one of the most successful encapsulations of an album’s interior meaning in the history of popular music, largely because it seems to imply so many different connotations in one fell swoop. Whilst portraying the purely transactional and hollow nature of the music business, it also seems to capture the self-destructive impulse of Pink Floyd’s tragic frontman, Syd Barrett, to whom ‘Shine On You Crazy Diamond’ was dedicated. Before the record has even been pulled from its sleeve, it seems to speak to the claustrophobic and shallow environment Pink Floyd found themselves in by the mid-’70s. Expanding ever outwards, the album can be regarded as something of an antidote to that claustrophobia. And so many years later, Wish You Were Here still has explosive power.

The songs that land on Wish You Were Here were composed whilst Pink Floyd were touring Dark Side Of The Moon around Europe. It wasn’t easy going. Whilst that album had cemented their popularity worldwide, the extensive tours it necessitated left Pink Floyd exhausted creatively, mentally and physically. As a result, the prospect of producing another album of the standard they had set themselves seemed a near-impossible challenge. The band’s early attempts to compose new material were characterised by apathy, weariness and quiet disintegration. But within weeks, the tide had started to turn, and Roger Waters began to establish a concept that would act as the catalyst for Wish You Were Here.

By 1974, Pink Floyd had the bare bones of three new compositions and went about honing them during the final leg of their European tour. One of these rough compositions, from David Gilmour, was little more than a four-note melodic pattern. Within those four notes, however, Gilmour found something which seemed to evoke the “indefinable, inevitable melancholy” of Syd Barrett.

The group worked together to develop the song fragment, transforming it into the album’s opening track ‘Shine On You Crazy Diamond’. The song triggered a creative surge and, soon enough, Waters, Gilmour, and Mason found themselves plunging into new and unfamiliar musical territory. In tracks like ‘Welcome To The Machine’ and ‘Have A Cigar’, for example, the group criticised the insincerity and hollow ideals of the music industry.

In this way, Wish You Were Here seemed to represent a new maturity in the band’s output. But, whilst the album won the hearts of many for its innovative use of synthesisers and sound design, some regarded it as a bitter lament that revealed an obvious lack of creative imagination. In contrast to Dark Side Of The Moon, Wish You Were Here seemed like the product of a band whose passion for their art had long since faded.

Today, however, the album seems an infinitely more intelligent record than Dark Side of The Moon. It’s true that it lacks the accessibility of that previous album, but it has a poignancy that never quite emerges in Dark Side. That same poignancy is heightened by the stories which surround the production of the album. One notable example is the story of Syd Barrett’s surprise visit to Abbey Road on June 5th 1976. Pink Floyd were putting the finishing touches on a mix of ‘Shine On You Crazy Diamond’ when an overweight man with no hair and shaved eyebrows walked into the studio. Gilmour presumed he was a member of EMI staff and, when he finally managed to identify his friend, was utterly horrified.

The band’s conversation with Barrett was normal enough, but it became clear that the former frontman wasn’t really there. He didn’t seem to recognise the relevance ‘Shine On’ had to him, and he eventually wandered away without saying goodbye. Waters was deeply upset by the experience of seeing his friend so drastically changed, and it undoubtedly affected the melancholy mood of Wish You Were Here.

Whilst fans are divided about whether ‘Shine On You Crazy Diamond’ is actually about Barrett, what is clear is that the album as a whole, captures the profound tragedy of Barrett’s decline. It is an album that grapples with itself, interrogating the sadness inherent to modern life.

Pink Floyd A Momentary Lapse of Reason (1987)

From progarchives.com

Review by Second Life Syndrome

I think it might be time. I know this might be shocking, but I think the prog community can finally forgive Gilmour for being a jerk. I think we can get over the fact that a non-original member of the mighty Pink Floyd was able to take over the revered name. I think we can mature as a community, people. It’s time that “A Momentary Lapse of Reason” finally be given the props that it deserves as the masterpiece that it is.

I think it might be time. I know this might be shocking, but I think the prog community can finally forgive Gilmour for being a jerk. I think we can get over the fact that a non-original member of the mighty Pink Floyd was able to take over the revered name. I think we can mature as a community, people. It’s time that “A Momentary Lapse of Reason” finally be given the props that it deserves as the masterpiece that it is.

I know that might be shocking. I know that might be hard to take. But this first album without Roger Waters is every bit the masterwork that “Dark Side of the Moon”, “The Wall”, and “Animals” are. The only Pink Floyd album that I consider better is “Wish You Were Here”, and that only by a hair. I understand that I have to explain myself.

“A Momentary Lapse of Reason” features all the mood, the casual atmosphere, the hard- hitting lyrics, and the instrumental brilliance of all the Floyd albums, but with an added complexity and eclecticism that floors me. The jazziness, the atmospheric instrumental perfection, the array of instruments used: these all tell me that this album needs to be recognized. This can be seen right from the beginning, as “Learning to Fly” contains classic Floyd rhythm and leaves an immense impression. “Dogs of War” brings the melancholy negativity that Floyd has often been known for, and it brings it with style and jazz. “On the Turning Away” gives us delicate melody and the tenderness of emotion that I find in “Wish You Were Here”. “Terminal Frost” is one of the best and most interesting instrumental tracks I’ve ever heard! I could go on and on, but I will only mention one more. “Sorrow” is possibly one of the top 10, if not top 5, Floyd songs ever recorded. From the massive drone of its guitars and its spectacular guitar solo to the funky, off-time beat and awesome bass, this track is killer.

Gilmour’s guitars were never better than on this album. His mastery is everywhere, and his perfection of the guitar solo is evident. Tony Levin shines with his groovy bass and his energy. Yes, Mason even convinced me here that he is one of the greatest drummers of all time, as his deceptively simple drumming is rife with incredible intricacies and exacting signature changes. John Halliwell is phenomenal on the sax, simply fantastic. This, then, is no Gilmour solo album. It might seem like that only because Gilmour became the sole vocalist (for the most part) and his guitar work is more prominent. That’s it.

Look, I understand. I don’t like it when a great band splits and the seemingly “unworthy” member gets to lead the band into the future. But, as subsequent albums and the sensational “Pulse” show us, I think Gilmour was the best choice. Hindsight is 20/20, right? Could Waters have done anything more than keep travelling his downward spiral of negativity? And, in all honesty, do you think Mason really wanted to lead this legendary band? Gilmour, then, was the best thing for Floyd, and “A Momentary Lapse of Reason” is simply one of the best Floyd albums ever made.

Review by SouthSideoftheSky

We all know the story; Roger Waters took more and more command over Pink Floyd around the time of The Wall and his complete control culminated on the very disappointing The Final Cut until the rest of the band had enough and they split up. Momentary Lapse Of Reason is the band’s comeback album and in my view a return to form. Roger Waters is no longer here and this fact was evidently very liberating for David Gilmour. This album is dominated by David Gilmour’s guitars and vocals and he sounds completely rejuvenated in both departments! His vocals are strong and his guitar sound was never as distinctive and powerful as this. Also as a songwriter, Gilmour had matured a lot and he had a hand in all the songs on this album, but he is helped out by several others. Songs like On The Turning Away and Learning To Fly give a strong indication of what was to come on the excellent follow-up album The Division Bell, for which Gilmour’s song writing skills would improve further.

A Momentary Lapse Of Reason is not just a comeback album after a longer absence, but a return to form after the disappointing The Wall and The Final Cut albums, and also, in a way, it is a transitional album; it is both backward-looking and forward looking at the same time. It is partly a return to the sound of Animals and Wish You Were Here, where Gilmour and keyboardist Rick Wright had a much larger influence, and partly also the birth of something brand new that would culminate with the excellent Division Bell (and the equally great live album PULSE). The titles of Dogs Of War and New Machine are probably not coincidental. Dogs Of War remind of Dogs from Animals and New Machine remind of Welcome To The Machine from Wish You Were Here.

It is a bit weird that Rick Wright is not listed as a full member of the band, but as a session musician! He finally became a full member of the band again for the Division Bell album and tour.

The title of the album possibly refers to the time when they let Roger Waters take complete control of the band. The period between Animals and The Final Cut was perhaps ‘a momentary lapse of reason’ on behalf of the other members?

Personally, I find A Momentary Lapse Of Reason better than many older Pink Floyd albums and a very good album in its own right with several good songs and a few excellent ones. The almost folky On The Turning Away being particularly noteworthy – one of Gilmour’s finest vocal moments ever!

Is this still really Pink Floyd? That seems to be the question, as it has been since Roger Waters left the band in 1985 to dip deeper into the sci-fi soup. Waters has since missed no opportunity to slag his former band mates as incompetent fakes. He would suggest that he was Pink Floyd, although judging from his overwrought, concept burdened solo albums, that notion should be put to rest.

Is this still really Pink Floyd? That seems to be the question, as it has been since Roger Waters left the band in 1985 to dip deeper into the sci-fi soup. Waters has since missed no opportunity to slag his former band mates as incompetent fakes. He would suggest that he was Pink Floyd, although judging from his overwrought, concept burdened solo albums, that notion should be put to rest. Standing almost in mockery of the swipes the band members have taken at one another is the new three-disc box set Crazy Diamond, which collects the decidedly eccentric post-Floyd musings of original member Syd Barrett. Barrett, as all Floyd devotees know, was booted from the band in 1968 during the making of A Saucerful of Secrets as he deteriorated mentally from excessive intake of LSD. In 1969 and 1970, he was encouraged by Gilmour and Waters, among others, to return to the studio. The erratic results were released over a period of time as The Madcap Laughs, Barrett and Opel.

Standing almost in mockery of the swipes the band members have taken at one another is the new three-disc box set Crazy Diamond, which collects the decidedly eccentric post-Floyd musings of original member Syd Barrett. Barrett, as all Floyd devotees know, was booted from the band in 1968 during the making of A Saucerful of Secrets as he deteriorated mentally from excessive intake of LSD. In 1969 and 1970, he was encouraged by Gilmour and Waters, among others, to return to the studio. The erratic results were released over a period of time as The Madcap Laughs, Barrett and Opel.

A wonderful album that I have enjoyed since 1973