Sly & the Family Stone Stand (1969)

From albumism.com

At approximately 3:30 a.m. on Sunday, August 17, 1969 at the Woodstock Musical Festival, Sly and The Family Stone took it to the stage. These days, I can’t imagine doing much of anything coherent at 3:30 a.m., but here, during the smallest of the small hours, the members of the seminal soul/funk/rock group got up and rocked a crowd of approximately 400,000 people.

At approximately 3:30 a.m. on Sunday, August 17, 1969 at the Woodstock Musical Festival, Sly and The Family Stone took it to the stage. These days, I can’t imagine doing much of anything coherent at 3:30 a.m., but here, during the smallest of the small hours, the members of the seminal soul/funk/rock group got up and rocked a crowd of approximately 400,000 people.

Sounding fresh and sharp as they would ever sound on stage, Sly and The Family Stone gave one of the best performances of the three-day festival and one of their greatest live performances as a band. At one point, they famously got the absolutely massive crowd chanting “HIGHER!” while throwing up the peace sign. Even listening to the audio, the electricity is palpable.

Countless historians and musicologists have written millions of words about the Woodstock concert and the associated sociological conditions that made it what it was, but I like to think those 50 minutes on stage by Sly and The Family Stone could be considered the high water mark of the high water mark of the late ’60s. During an event that’s become synonymous with music serving as the vessel of peace, love, and togetherness, Sly and the Family Stone radiated all three.

Part of what brought the collective to that moment in time was Stand!, the group’s fourth album, released 50 years ago. The San Francisco-based assemblage of musical pioneers had been releasing albums since the mid-1960s. The gathering of musical minds became proprietors of psychedelic soul in 1966, led by former DJ and overall genius multi-instrumentalist Sylvester Stewart a.k.a. Sly Stone. One of the first notable bi-racial bands that also featured men and women, their ranks included uber-talented bassist Larry Graham, as well as Stone brother and lead guitarist Freddie, and Stone sister Rose, as a vocalist and keyboard player. The line-up also included drummer Greg Errico, trumpeter Cynthia Robinson, and saxophonist Jerry Martini.

Prior to the release of Stand!, the group was best known for rollicking soul and rock jams like “Dance to the Music.” Though they had earned commercial and critical success, the band was coming off the release of their somewhat disappointing third album Life, which had hit shelves in July of 1968. Life was a solid, reasonably light album that was fun but didn’t really break any new ground or sell nearly as many copies as Dance to the Music.

Stand! was Sly and The Family Stone’s best and most commercially successful album of their career. It went platinum in less than a year, eventually selling three million copies and spawning the #1 chart-topping “Everyday People.” The album is one of the defining pieces of musical work of the late 1960s. Whereas the group had dabbled in themes of unity and peace on Life, these subjects became the super-text of Stand!

I was not alive when Stand! became a musical and cultural force. I learned about this album and Sly and The Family Stone from my father, who played it pretty frequently when I was growing up. Over the years, as I’ve come to learn about and listen to the music produced from that era, Stand! endures over all. Even within a year that featured as many great, important albums as 1969, Stand! remains at the top of the heap.

We live in deeply cynical times. We trade in sarcasm and skepticism as easily as we breathe oxygen. So it’s easy to perceive genuine sentiments expressed on Stand! with a jaundiced eye. But the album’s absolute sincerity is refreshing. Stand! is inspiring without ever being didactic, simplistic, or preachy.

Stand! crystallized the spirit of the late ’60s like few other albums have done. It’s a tribute to love, unity, optimism, and equality. Sly and The Family Stone express a deeply held belief that things could and would get better, that Black and white populations could love together in harmony. That you could stand up to the Goliaths in the government and make a difference. That people could make a difference in turning the world into a better place for everyone.

This worldview is typified in the album’s title track. The song leans hard into its message of empowerment, evoking imagery of little people standing tall and giants about to fall, all while encouraging people to remember that they’re free if they want to be. “Stand” is often remembered for its frenzied final third, where Stone decides to shift that tone of the song, recording a thrilling gospel-inspiration coda, with chanting vocals, blaring horns, and pulsing organs.

“I Want To Take You Higher,” the B-side to the single of the title track, is a blistering, blues-heavy ode to the power of music. Amongst the heavy guitars and chants of “Boom lakka lakka!,” Sly and his family implore the audience to allow themselves to be taken to another plane by the sheer force of the composition. “Sing a Simple Song” is another exemplary entry to Stand!. Though the lyrics may be simple by design, the instrumentation is complex and layered. The song’s use of vocals is also excellent, with the band expressing itself through chants and yells.

“Everyday People” is a magnificent piece of work—a perfectly constructed traditional pop song. Before it was appropriated as a jingle to sell Volkswagens, “Everyday People” roused its audience with its message that people could respect each other’s differences and live together. It says more in under two-and-half minutes that many songs twice its length ever attempt. The song is also notable for featuring one of the first instances of Graham’s “slap” bass-playing style, which he’d utilize and perfect throughout his career as a member of the band and as a solo artist.

Even edgier, rougher fare like “Don’t Call Me N***er, Whitey” maintains an underlying message of understanding. The lengthy jam is mostly instrumental, characterized by sinister horns and gritty guitars, as well as a solitary verse by Rose Stone. In lieu of other verses, Sly Stone makes frequent use of the vocoder, transforming his voice into a harmonica-like instrument.

The band really decides to cut loose with “Sex Machine,” the 13-minute instrumental track. Whereas “Don’t Call Me…” is a more structured endeavor, “Sex Machine” is a free-flowing rock/funk jam session. Stone again makes ample use of the vocoder, as all the other members of the group are given a solo, each allowed to cut loose and improvise.

“You Can Make It If You Try” is another stirring call to action, designed to encourage the audience to work to fight against oppression in its many forms. The simple poetry of “Time’s still creeping, especially when you’re sleeping / Wake up and go for what you know” is really hard to top. The song is also one of the most musically interesting compositions, with its plucky guitar, rugged horns, and energetic organ breakdown about halfway through the song.

After Stand!, for a brief time, things got even better for the band. The Family Stone released singles for “Hot Sun in the Summertime,” “Everybody is a Star,” and “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin).” The Woodstock performance soon followed. Things began heading downhill as 1969 turned to 1970, as the goodwill of the 1960s quickly curdled into something very toxic. It hit few artists harder than Stone.

People are often obsessed with the protracted “end” for Stone because it seems to be “ending” so incredibly badly. Looking back at the legendary bandleader’s fall from grace is an exceedingly depressing exercise. During the 50 years that have followed the release of Stand!, I’ll be generous and suggest that a little under 40 of them have been a complete and utter mess. They’ve been marked by disillusionment, bitterness, anger, isolation, and seclusion. And drugs. Lots and lots of drugs.

Stone never seems to have “outgrown” his drug addiction. His life following the release of Stand! has been marked by rampant cocaine and PCP abuse. The stories of him carrying around a violin-case full of narcotics have achieved legendary status. There are countless tales of scheduled concerts where he performed hours late or not at all. There’s a general sentiment of how he alienated himself from nearly everyone he loved.

Stone’s free-fall has been continual, proceeding unabated by the passage of time. There has been no sequence of events that plays like the last 10 minutes of a Behind the Music episode or the last 20 minutes of a traditional musical biopic. The hero never hit the proverbial rock bottom, experienced a spiritual or musical redemption, and moved on the next phase of his life. There doesn’t appear to be a bottom to this pit.

Sly Stone has long become a recluse, only occasionally re-surfacing. He notably reappeared during Sly and the Family’s Stone induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1993, surprising everyone in attendance when he joined the rest of the Family Stone on stage. That was one of the good moments. There haven’t been many.

Closer to the norm was his brief appearance during the 2006 Grammy Awards ceremony during a tribute to the band. Sporting an embarrassing blonde Mohawk, he played “Take You Higher” while hunched over a keyboard and warbled part of a verse. After about a minute and a half , he got up, waved to the crowd, and left. Even worse was a thoroughly embarrassing 30-minute “performance” at the Coachella Music Festival in 2010. Stone ranted and raved at the audience about how his former manager was stealing from him, how he could only afford to live in motels, and how he could still afford to buy new shoes.

Some people would say that there’s something poetically tragic about that man who spearheaded a group known for embodying peace, love, and understanding becoming the living embodiment of every way that the ’60s went wrong. Personally, I see only sadness and ignominy. And I wish it won’t keep ending this way.

Stand! remains a timeless piece of art, as moving now as when it was first conceived. That’s what I choose to still celebrate, as I remember Sly Stone and his crew as musical titans who walked the Earth. There may never be another band like them, which is sadder than I can imagine.

Sly & the Family Stone There’s a Riot Goin’ On (1971) – ‘A nation’s fabric unravelling’ – stars on Sly Stone’s There’s a Riot Goin’ On at 50

From theguardian.com

Musicians from Nile Rodgers to Johnny Marr, Moor Mother and Booker T Jones discuss Sly and the Family Stone’s drug-fuelled landmark in US social commentary

Sly and the Family Stone emerged in mid-60s San Francisco with a lineup that was trailblazing in its diversity and euphoric in its fusion of rock, soul, gospel, funk, jazz and psychedelia. After acelebrated Woodstock appearance in 1969, the outlandishly stylish bandleader Sly Stone retreated to a Los Angeles attic and much-mythologised drug-fuelled circumstances to record There’s a Riot Goin’ On, an album rich in militant social commentary and groundbreaking production techniques.

Sly and the Family Stone emerged in mid-60s San Francisco with a lineup that was trailblazing in its diversity and euphoric in its fusion of rock, soul, gospel, funk, jazz and psychedelia. After acelebrated Woodstock appearance in 1969, the outlandishly stylish bandleader Sly Stone retreated to a Los Angeles attic and much-mythologised drug-fuelled circumstances to record There’s a Riot Goin’ On, an album rich in militant social commentary and groundbreaking production techniques.

It is now regarded as one of the 20th century’s finest albums in any genre. As a vinyl reissue celebrates its half-century, stars from different generations discuss the album’s impact on them, and how it continues to reverberate in pop music to this day.

Nile Rodgers

The statement that the album made to young Black America was one of positivity. A lot of the problems that we were facing – and unfortunately continue to face – we were starting to talk about and deal with directly in our pop music. Black artists traditionally didn’t have the freedom to do that, unlike white artists, but now Sly was at the vanguard of that. It felt like our time had come. You sure can dance to Family Affair, but it talks about the beautiful mosaic of people on Earth. The album was a revolutionary statement. It was liberating and gave a young artist like me, coming up, the ability to dream.

PP Arnold

I heard about Sly when I was in the Ikettes, touring with Ike and Tina Turner. He was a DJ playing the Beatles and the Stones alongside Ray Charles, soul and R&B. The Family Stone were into fusion, and it felt very connected to unity, peace and racial equality. They were the first band to have a multiracial lineup of men and women. When Sister Rose [Stone, vocals] joined for Dance to the Music and did those great gospel harmonies with [the girl group] Little Sister, it changed the whole sound. They had hippy psychedelic pop, soul and rock. Every album got funkier and they changed the scene. They sang about the truth of what was going on.

Towards the end of the 60s, civil rights, the Martin Luther King assassination and Vietnam affected everybody, and the drugs came in and changed things. You’d hear about death-threat rumours, gangsters, rip-offs. Sly had fallen out with the original band, and on songs like Just Like a Baby you can hear his vulnerability. (You Caught Me) Smilin’ is sad even though he’s smiling, because he’s lost. The drugs changed Sly’s voice, so on There’s a Riot Goin’ On there’s a gravelly, haunted vibe. It’s urban blues, but the love, innocence, fun and harmony is still in there.

Greg Errico, drums, Sly and the Family Stone

All the stories about the Riot sessions are true. It was a tumultuous time. The group was splintering and there was huge pressure on Sly to make another record just as we were breaking up. We had cut Family Affair and Thank You For Talkin’ to Me Africa with the original band the year before. Then Sly wanted to do it all himself, maybe realised it wasn’t such fun but couldn’t back down.

It went from a traditional studio to the attic of his house – with all the chemicals. He’d knock on my door at 3 or 4am and say: “Come on, I’ve got this part. Get up, let’s start recording!” Other times he’d call the sessions off. Eventually I stopped going, which got him into using the drum machine. It was the kind of thing the guy in the lounge of the Holiday Inn would use to make lame music, but Sly used it very creatively. Starting the machine’s rhythm on an off beat turned the beat inside out and gave a unique sound.

The music was darker because times were darker. When I first heard the finished album, I had a little attitude – “He should have stuck with us” – but gradually I realised it was really creative and lyrically he was talking about what was going on. I started listening with a smile on my face.

Bobby Gillespie, Primal Scream

The earlier hits such as I Want to Take You Higher or Everyday People were transcendentally joyous party records, affirmations of unity, whereas There’s a Riot Goin’ On is modern blues, a very dark record that reflected the fear, paranoia and disappointment of Black America. There was poverty, homelessness, drug addictions and the Vietnam war. Martin Luther King and Malcolm X had been shot. The American state was waging war against the Black Panthers. Marvin Gaye’s What’s Goin’ On was a plea for some kind of better day, whereas Sly’s record had a negativity to it. He holed himself up behind a wall of drugs and withdrew into himself.

The earlier hits such as I Want to Take You Higher or Everyday People were transcendentally joyous party records, affirmations of unity, whereas There’s a Riot Goin’ On is modern blues, a very dark record that reflected the fear, paranoia and disappointment of Black America. There was poverty, homelessness, drug addictions and the Vietnam war. Martin Luther King and Malcolm X had been shot. The American state was waging war against the Black Panthers. Marvin Gaye’s What’s Goin’ On was a plea for some kind of better day, whereas Sly’s record had a negativity to it. He holed himself up behind a wall of drugs and withdrew into himself.

It’s very dense: a hermetic sound, not a lot of air in the production. He couldn’t write those joyous anthems any more. Things were too dark, socially and personally. There’s a resignation and understated anger to it, like Family Affair: “One child grows up to be somebody that just loves to learn / And another child grows up to be somebody you’d just love to burn.” Running Away is almost about addiction, maybe a warning to himself. It’s a suffocating record, but addictively intoxicating.

Booker T Jones

I saw Sly and the Family Stone at the Memphis Mid-South Coliseum in 1966 or 1967. It was just amazing. They had inventive horn lines, electronic sounds on the guitar and a Hammond organ. It was rock’n’roll and R&B, with this boom-boom Sly shuffle groove which was like a locomotive. [The bassist] Larry Graham played high on the fretboard. They had songs with one chord and others that were structurally liberated, a kind of restrained wildness. The hits were so fresh. The social commentary made them important and poignant, with spiritual context. The message in Everybody Is a Star is so simple. His music had a knowledge of the human self.

There’s a Riot Goin’ On drew on the music they made earlier, but it has a different dynamic. Sly was mixing genres and sounds from different sessions in the way we now use sampling. When he sings “My only weapon is my song”, in Poet, he recognises that we’re involved in a struggle and the songwriter has a responsibility to the world. To me, Family Affair addressed the big family of the human race and the caste system, which was going on right under our noses. Some people were thriving and others were being destroyed. In 1971, there was some bad shit going on, but he had the dark with this undiminished joyfulness. He was like a JS Bach or Duke Ellington, but in a different genre.

Dennis Bovell

When I was 17 or 18, this was the most progressive music around in terms of social comment and badass bass lines. It’s a revolutionary masterpiece and everything that came after has been touched by it. Larry Graham had invented thumping with the thumb and slap bass, and the horn riffs were to die for.

Sly was the funk Hendrix. He was carrying a multiracial flag and some Black people didn’t want him playing with white guys. When I faced the same attitudes in [the multiracial late-70s band] Matumbi, we performed Thank You Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin from Riot as a reggae song. I believe the opening line – “Staring at the devil, looking at his gun” – was based on a real life encounter with a cop.

In the 70s, one of my friends brought Sly over to play a venue in Cheam [suburban south London]. They drove him to the gig in the limo and Sly said: “Take me back to the hotel. We don’t do bars.” He stood for no nonsense.

Suzi Quatro

When Dance to the Music came out, I was exactly the right age to listen to the radio and go: “Yeeeeaaaahhh!” Each instrument was like a little solo. He had the charisma, the moves, the horns, and half the band was actually his family. There’s a Riot Goin’ On was a surprise, but I like it when artists do that. Creativity doesn’t follow rules.

I do wonder if he had the tools to cope with his fame. When someone like Sly, who was quite normal, gets famous, in his mind, [being] the not-famous one isn’t good enough – so he tries to become the famous one and obliterate the normal person.

Steve Vai

When I was nine or 10, Sly and the Family Stone’s Greatest Hits felt like an awakening, but even at that age it was obvious to me that there was a profound shift in the music for There’s a Riot Goin’ On. Later in life, I saw how that record was a perfect storm. It was driven by the political protest and social transition at the time, but also his inner demons and vast departures in the production technique.

Sly was on a paranoid downer and started surrounding himself with thugs and marching to the beat of his own drum, alienating the band and bringing in Ike Turner, Bobby Womack and Billy Preston. Often, when a band or artist undergoes a big transformation, they can be a little bit more raw and honest. It can be both quasi-disastrous and have great merit, and that’s how I see Riot. His brilliance snuck through the debris.

He had the nerve to open it with Luv N’ Haight, which basically falls apart. On some songs you can’t even hear the vocals in places, but that adds to the mystique. When you’re that creative, you see things so differently you’re almost hallucinating. The dark overtone expresses the way he was digging deep into his feelings, but you can feel the energy and be inspired by it. And a lot of people were.

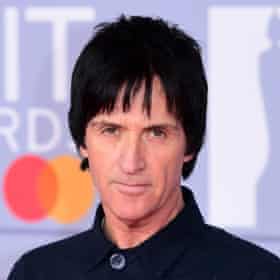

Johnny Marr

I got into There’s A Riot Goin’ On towards the end of the Smiths. I was aware of the hits, but I’d never heard anything like it before. Sly had invented his own form – part-gospel, jazz, experimental proto-funk – and was way ahead of his time with the idea of a multiracial, multigender band. Family Affair is so laid back he’s almost falling out of the grooves.

Greil Marcus called Sly Stone a “cultural politician”, but for me the album puts out a feeling of complete creative freedom – and there’s a power in that. For one of the biggest cultural figures in America to retreat into his own cocoon is very single-minded. The message needed to be heavy in the same way as it did in hip-hop in the 90s, but while the vibe is coming from the death of idealism, there’s not one song that’s explicit. Mere proselytising wouldn’t have connected.

It’s genuinely countercultural and revolutionary and takes soul to the cosmos. People say the record sounds like it does because of his drug use, but you could argue that the drugs facilitated the vision. I don’t think such an important record was made by accident.

Sananda Maitreya

Hearing Riot for the first time led to the rebirth of my own horizons. It’s the perfect bookend to an era rife with inquiry and innovation. Its bold, brash intimacy predates the DIY ethos of hip-hop and lo-fi and its naked abrasions foreshadow the emotional landscape of punk and pushed jazz into another moulting of its feathers. It took massive balls to realise such a visionary achievement, one as mind-blowing then as it is now. It’s a soundtrack of the unravelling of a nation’s fabric, a document of a poet sharing his personal vision of hell but demonstrating that a phoenix from the ashes can shake off the sparks and turn them into stars.

Baxter Dury

He’d mastered his African and American influences and converged with pop and was galloping somewhere else. It was badly reviewed initially, and you can see why – because it was so dense. He was splitting apart, but the album captures the moment between the brilliance and the crash. Marvin Gaye’s album asked What’s Goin’ On and Sly answered There’s a Riot Goin’ On. He was perhaps more politicised, but devoted to cocaine and PCP [angel dust]. Guns and drug dealers at the house. He had a pit bull called Gun, which would bite anyone who went near him. It’s a grand story of decadence, but at the same time very sad. It robbed him of the great music he might have made later, but Riot – some of the best music ever made – split the atom.

Moor Mother

I was trying to learn about the music that came before [Riot] and came across a clip of Sly and the Family Stone doing I Want To Take You Higher live. I couldn’t believe how diverse and how good they were. We come from these kind of segregated places in terms of who’s allowed to do what or play what and he just didn’t recognise those boxes. The sense of freedom was so empowering and has inspired me enormously in terms of being free and taking in everything. He wasn’t bound by sound.

The music and lyrics on Riot are like a collage. It’s like walking through different neighbourhoods, but makes you realise how connected everything is. It jumps around because we’re all included and it’s about raising our vibrations and calling us to attention. I love what hip-hop has been able to do with his music; tracks like the Roots’ Star, sampling Everybody Is a Star. There are no bad samples from Sly and the Family Stone. The music sounds fresh after 50 years because it’s the truth. When you hear Sly, you go to a different place.

Howard Devoto, Buzzcocks / Magazine

A friend who worked in a record shop in Leeds gave me a white label of Riot because it “wasn’t his thing”. I liked the singles, Family Affair and Running Away, then filed it away for a couple of years. A few years later, after I’d bought Funhouse by the Stooges, I dug it out again. I remember my flatmate Mark Roberts – who filmed the Sex Pistols gigs in Manchester – and I looking at each other and thinking: “This is a great record.” The darkness, decadence and nihilism resonated with what was going on in me, pre- and then post-punk. The emotional and spiritual terrain felt like familiar turf.

It fascinated me how Sly had taken an earlier, upbeat-sounding song – Thank You Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin – and turned it into Thank You For Talkin’ to Me Africa, almost a relentless dirge. We covered it in Magazine, rebranded with its original title, and performed it at the end of gigs as a “Thanks but no thanks for making me suffer it all again”.

I love the album’s nursery rhymes, childish chants, gobbledegook, croaked vocals, mumbling and slurring, rasped asides. Time is my favourite Sly song of all: utterly exhausted, shrieking desperately. The guy sounds turned inside-out. It’s all unhinged – but great tunes and musicianship shine through.

Mica Paris

I always say the true artists and revolutionaries in music are the ones that create a sound that everyone else copies. In those days Black music was compartmentalised as jazz, soul or gospel. Chuck Berry and Jimi Hendrix were important because they were Black musicians playing rock, but Sly came from nowhere with a really funky soul-rock sound and all these genres meshed into one. Places where musicians wouldn’t normally go. He was one of a kind, totally eccentric, stylish and out there. If it wasn’t for Sly, there wouldn’t be George Clinton, Prince, Rick James. So many borrowed from Sly, but he was the first.

Dave Okumu, the Invisible

One of the first two albums I bought was De La Soul’s Three Feet High and Rising and they’d sampled Poet from There’s a Riot Goin’ On. The album has since become part of my DNA. So many ideas and so much that has inspired me seems to originate from this record. It’s the ultimate archive. I’m fascinated by the process where your creativity takes you through limitations and into a vision that seems out of reach, but where magical and mysterious things happen.

Lee Fields

Sly and the Family Stone took it to the edge in technology and music. I Want to Take You Higher was a gospel experience in pop. Riot was gospel, west coast, rock, funk and all sorts on the periphery. He was a millennium away from the rest of us normal human beings musically. Prince and Michael Jackson took his path with technology, along with everyone else. If you listen to music today, you can hear Sly.

Nicolas Godin, Air

There’s a Riot Goin’ On must be on of the first home studio albums. John Phillips from the Mamas and the Papas had installed recording gear in Sly’s mansion in Bel Air, and the musicians just took cocaine and made the record themselves. Sly bounced so many tracks down that the record ended up as lo-fi. Family Affair is the first [US] No 1 single to feature a drum machine, the Maestro Rhythm King. I have the exact model. It’s primitive, but grooves like a drummer, and he mixed it with live percussion – which of course subsequently became standard. It’s a chaotic album, with free, talented skilled musicians doing everything they have in mind. Half a century later, it’s an album we all listen to.

Steve Gunn

This album really spoke to me when I was younger, so it was fascinating to learn more about how it was made and the risks that were involved. He’d closed everything off to go into a different place of darkness and hope. He was tired of people giving him a hard time, probably burned out by the triumph at Woodstock and with huge labels breathing down his neck, waiting for this music. So he locks himself in his house and comes out with a fearless, experimental, mysterious record. He’s got a No 1 single [Family Affair] on it, nine-minute songs with drum machines, and the title track is a second of silence because he didn’t want a riot on the record.

Speech, Arrested Development

In the 90s I kept hearing these great drum sounds on hip-hop records and realised they came from Sly and the Family Stone. Their multiracial, multigender lineup was crucial to our evolution: without them, there would be no Arrested Development. Everyday People gave us a chorus for one of our songs [People Everyday] and so they became very dear to me.

There’s a Riot Goin’ On is a ray of sunshine. It shows the humanity of the Black experience in a way that a lot of soul music of that time and today doesn’t. For me, Family Affair is about the ups and downs within a family. Just Like a Baby is so vulnerable and Running Away is so light and airy, yet it’s about hard times in American history for Black people.

After the assassinations [of Martin Luther King and Malcolm X], the record to me is Sly Stone as an African American man retreating to the one common denominator, our humanity. Africa Talks to You (“The Asphalt Jungle”) is letting people in the asphalt jungles of Harlem or St Louis or Detroit know that there is hope and a sense of belonging. It was a brilliant, experimental exploration of sound and textures to wake us up.

Lee Tesche, Algiers

This record comes up a lot in conversation in the van or the studio, particularly with production. I remember listening to it on the way to school with my mom. I turned the band on to it and it seeps into what we’re doing. Sometimes, when there’s a lot of pressure, you rebel. You can hear the sound of stuff splitting at the seams. He had such a cavalier attitude – the weird panning, tape glitches and erratic sound levels, or the yodelling on Space Cowboy. The hi-hat sounds almost electronic, like you’d hear with later-70s bands like Suicide. For the vocals, he used a wireless lapel microphone and recorded them in bed. They’re so laid back, but raw and in your face.

Still waiting for the book.