Oasis Be Here Now (1997) – Flattened by the cocaine panzers – the toxic legacy of Oasis’s Be Here Now

From theguardian.com October 2016

Oasis released their third album to rave reviews and colossal sales. Yet it soon came to be seen as a disaster, and the embodiment of hubris. The critics behind those five-star reviews explain what happened

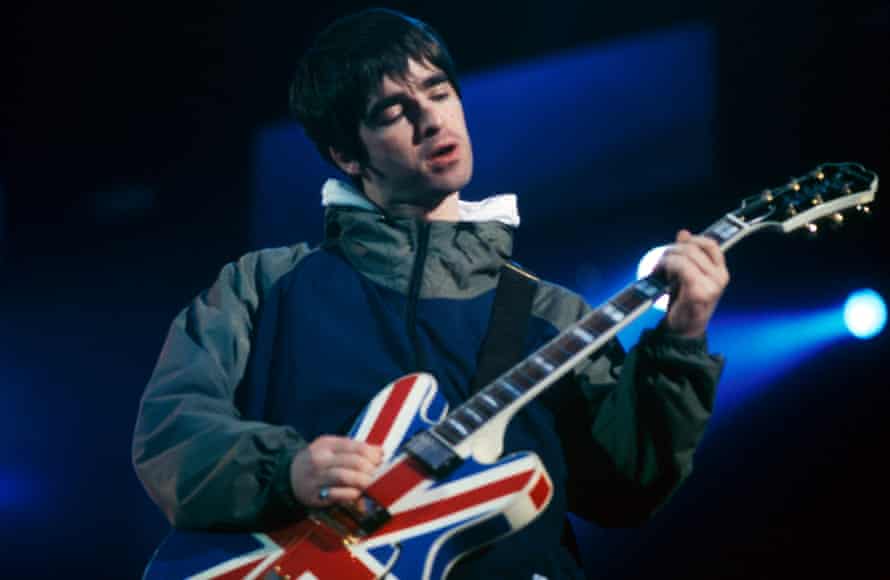

On the evening of 20 August 1997, BBC1 broadcast Right Here Right Now, a panegyric to Oasis on the eve of their third album, Be Here Now. Hyperbole abounded. “I think it’s the best thing we’ve done,” said guitarist Paul “Bonehead” Arthurs. Oasis were “the most important rock’n’roll band in the world,” claimed Liam Gallagher. “We still want to eclipse every single musician in this country,” said Noel Gallagher. “Because we want to. Because we can. Because we’re the best.”

For a little while, Be Here Now demanded superlatives. With more than 696,000 copies leaving the shops in its first week, it became Britain’s fastest-selling album ever, until Adele released 25, 18 years later. Its path was paved with five-star reviews, like petals thrown beneath a Roman emperor’s feet. Footage of excited fans clutching copies made News at Ten, leading anchorman Trevor McDonald to intone the phrase “mad for it”. On the BBC news, a very young Peter Doherty, queueing to buy his copy, cited Umberto Eco in his analysis of the group.

No album in history has experienced such a swift and dramatic reversal of fortune. Be Here Now was reframed first as a disappointment and then as a disaster. It burned out quickly, falling well short of the sales achieved by 1995’s (What’s the Story) Morning Glory, with many copies ended up in secondhand racks. Noel himself quickly disowned it, dismissing it in the 2003 Britpop documentary Live Forever as “the sound of five men in the studio, on coke, not giving a fuck”. (Only Liam remained loyal: “At that time we thought it was fucking great. And I still think it’s great.”)

As Be Here Now returns in the form of a deluxe box set, and the band’s story is retold in the documentary Oasis: Supersonic, the album still inspires extreme reactions. If it couldn’t be Britpop’s zenith, then it must be the nadir. It can’t be just a collection of songs – some good, some bad, most too long, all insanely overproduced – but an emblem of the hubris before the fall, like a dictator’s statue pulled to the ground by a vengeful mob. The glowing reviews have become an opportunity for schadenfreude: evidence that music critics had, at best, lost all perspective and, at worst, deliberately misled their readers. “Right here and right now, this is the place to be,” trumpeted the Daily Telegraph. Mojo’s reviewer was even moved to patois: “This is Oasis’s World Domination Album. Dem a come fe mess up de area, seeeeeeeeerious.” In hindsight, the hysteria resembles a mass frenzy. “It’s almost like Big Brother,” says Alex Niven, author of a book about Oasis’s 1994 debut Definitely Maybe. “You were watching something crass and horrible but it was compelling and you had to watch it to get a sense of what Britain was like at that moment. It was like a performance of the collective psyche.”

I asked four of the critics who praised it – Paul Du Noyer (Q), Roy Wilkinson (Select), Paul Lester (Uncut) and Taylor Parkes (Melody Maker) – what happened and whether something like it could happen again. The starting point in revisiting the album is the acceptance that in 1997, Oasis were woven into Britain’s cultural fabric like no other band since the Beatles. Definitely Maybe permanently moved the goalposts for alternative rock in general and Creation Records in particular. (What’s the Story) Morning Glory was simply unavoidable. Wilkinson remembers hearing a pub full of pensioners sing along to Wonderwall when it came on the jukebox. “It seemed like an everyperson record,” he says. “There was a universality.” As Lester wrote in his review: “Much of the pleasure with Oasis is bound up in the shared historical moment … Like those other mid-90s newcomers, Friends, the internet, Spice Girls and the lottery, Oasis have managed to infiltrate British life in record time.”

“There are good populisms and bad populisms,” Niven says. “In the mid-90s, there was a sense that you might just have a good populism, and Oasis seemed to embody that. It nodded at sport and working-class culture and the heritage of the counterculture. Obviously, it wasn’t substantial enough so it didn’t realise its potential, but there is something valuable in that idea. I’m not sure we’ve had a collective moment on that level since. You can only get those moments when there’s a hovering suggestion of a genuine democratic breakthrough, as there was in the 60s and the mid-90s.”

Oasis’s everyman sensibility couldn’t survive the sudden flood of money and fame, unprecedented for a band from the independent scene. Noel’s new milieu of mega-gigs, celebrity parties, tabloid ubiquity and champagne at No 10 did his muse no favours. Oasis’s earlier songs had an exhilarating underdog hunger, but Be Here Now was mostly written and demoed at Mick Jagger’s villa in Mustique with a vast new audience in mind. “You start off writing songs that you’re not sure who’s going to hear them,” Noel told author Daniel Rachel. “Then, when I tried to write the next batch of songs, you’re like: ‘We’ve got 20 million fans in the world.’”

The box set reveals an intriguing vulnerability in the demos. Stand By Me has the weary tenderness of Half the World Away, and Noel’s jaundiced acoustic version of the Beatles’ Help! sounds like a cri de coeur: “And now my life has changed in oh so many ways.” That quality was flattened in the studio by the cocaine panzers, as songs were elongated and smothered in up to 30 layers of guitars. Repentant producer Owen Morris later summed it up thus: “Massive amounts of drugs. Big fights. Bad vibes. Shit recordings.” He called the final mix – a bludgeoning, airless wall of noise – “an utter disgrace”.

Before this self-conscious gigantism bedazzled critics, it bedazzled Noel and Morris. All Around the World was a white elephant based on a catastrophic misunderstanding of Hey Jude and the comeback single D’You Know What I Mean? was more rally than song. “It was massively, nuttily assertive: listen to me!” says Wilkinson. “But what was it saying? Nothing. It’s a blank space. A void.” Tim Abbot, then the marketing director at Creation, used an analogy from visual art: “They came down as little matchstick men and became a Koons.”

Noel’s pre-release interviews struck an oddly ambivalent note (“This record ain’t going to surprise many people,” he told NME), but there was nobody to echo his reservations. “Everyone’s going: ‘It’s brilliant!’” he later said. “And right towards the end, we’re doing the mixing and I’m thinking to myself: ‘Hmmm, I don’t know about this now.’” According to Oasis’s former press officer, Johnny Hopkins: “There were more hangers-on, constantly telling them they were the greatest thing. That tended to block out the critical voices.” For anyone invested in Oasis’s continued success, Be Here Now was too big to fail.

Alan McGee, Creation’s pathologically ebullient founder, told the press it was “absolute genius” and would sell 20m. But Oasis’s management firm, Ignition, was keen to manage the hype while thwarting the new threat of internet leaks, leading to neurotic secrecy. Hopkins first heard Be Here Now, alongside other key personnel, at Noel’s north London home, Supernova Heights. “We were sat around his dining table,” he remembers. “It felt a bit like a board meeting. There was a massive weight of expectation so it was really hard to hear it as a record in its own right.”

Ignition waged war with radio DJs and fan websites and required anyone handling advance copies to sign a non-disclosure agreement that barred them from even discussing it with anyone else. NDAs are commonplace now, and often more extreme, but to receive one from Creation in 1997 felt absurd. “The secrecy was hilarious,” Parkes says. “It was ludicrously self-important and it was only going to breed resentment.” Marcus Russell of Ignition later admitted: “I don’t think that was the right way to go about it.”

Any resentment, however, was outweighed by the desire of publications to keep their most bankable cover stars on side. Parkes remembers his originally ambivalent review being shorn of its most negative lines by his editor. “The pressure on critics was unprecedented. Prior to that, the music press could be honest because the industry had nowhere else to go, but now it had lots of other places to go. The music press was required to hold its nerve and it didn’t. It was embarrassing. It is not the job of the reviewer to pick out the records that are going to sell the most copies and praise them.” (“We wouldn’t have denied magazines interviews just because of bad reviews,” Hopkins says.)

Another factor was the music press’s embarrassment over its lukewarm reviews of What’s the Story. Lines such as “Don’t Look Back in Anger disappoints” (Melody Maker) and “Wonderwall achieves no real lift-off” (Q) looked out of step when the whole country was singing those songs. “The unspoken thing was that Melody Maker had given the last album a tepid review and it was going to make damn sure that didn’t happen again,” Parkes says.

Du Noyer, however, doesn’t recall any editorial pressure. He was genuinely rooting for Oasis to extend their hot streak. “I really hoped it was going to be a great record because I liked what Oasis represented,” he says. “I thought they were a thoroughly positive presence in national life.” Only when he saw the finished artwork’s preposterous tableau of timepieces and rock star bric-a-brac did he think twice. “I thought, bloody hell, this is a confused piece of work that’s trying to say so many things that it says absolutely nothing. Had I seen it, I might not have given them the benefit of the doubt.”

Wilkinson was also carried away by his fandom. “I was definitely on their side. There weren’t many bands who were demonstrably from a council estate background. The way they became part of the establishment was pleasantly absurd. I remember thinking in my heart of hearts there was something not quite right about what I was saying, but such was the phenomenal momentum you did want it to keep going – for them and the wider world. That made me err on the side of generosity.” He laughs. “I was completely wrong, of course, but at least it was hysterically bad to the extent where it’s remarkable.”

Be Here Now’s inevitable success warped the usual critical parameters. Reviewers weren’t so much analysing music as bearing witness to a phenomenon and seeking to prolong a collective high. They noted the record’s flaws – nonsensical lyrics, a stolid resistance to new ideas – only to sweep them under the rug of its presumed popularity, talking of “yet another 11 songs the slightly sozzled world will be bursting to sing” (NME) and “arenas full of waving scarves and flaming cigarette lighters across the planet” (the Observer). Translation: several million Oasis fans can’t be wrong.

“I was caught up in the excitement of it all,” Lester says. “I’m so sorry to everybody for that review, but the enormity of it was captivating. We were reviewing a moment in history and staking our part in it. It was like seeing the great behemoth of a spaceship in Close Encounters. You felt awed into submission.”

“You want the record to be good because you’re into the band,” says Hopkins. “And you want it to be good because that means it’s going to sell well and that’s going to help the magazines sell well. But I was surprised that there wasn’t a dissenting voice. When a band gets to that level, there’s always someone who says, ‘Hold on a minute,’ but there wasn’t [for Oasis].”

Be Here Now’s reputation lasted only slightly longer than the effects of a line of cocaine, but its sudden collapse can’t be pinned on the music alone. Oasis’s imperial phase coincided with several national developments – including New Labour’s unstoppable ascent, Euro 96 and Britpop in general – that fostered bullish optimism. Be Here Now arrived just as the tide was turning. The afterglow of Labour’s election victory was fading and, 10 days after the album came out, Princess Diana died. The connection may seem suspiciously neat, but Niven remembers the national mood changing. “Be Here Now was a bit late,” he says. “It felt like a slightly different era. That mid-90s moment had definitely passed.” More melancholic rock albums, such as Radiohead’s OK Computer and the Verve’s Urban Hymns felt far more relevant than Be Here Now’s triumphalist roar.

“The Oasis phenomenon had grown to astonishing proportions and it didn’t occur to me that it could go into reverse so abruptly,” says Du Noyer. “The backlash isn’t something I foresaw or understood. I don’t think anyone’s ever wrong to like or dislike a piece of music, but I think I was wrong in misreading the way the public mood was going to turn. Britpop was running out of steam and Be Here Now was the canary down the coalmine that told us this great movement in which we’d all invested such hopes wasn’t really going anywhere.”

Be Here Now’s mind-addling properties were specific to 90s Britain at its bombastic peak but similar groupthink occurs today whenever a major artist receives a gush of overnight reviews from critics who seem to be marking an event rather than unpacking the music, which they will have heard under more restrictive circumstances than those Oasis reviewers – hear it once, then get the review out while people are talking about the record. Might one of those albums one day inspire an equivalently drastic U-turn?

“You can easily imagine that happening with a Kanye or Frank Ocean album,” Lester says. “You’re reviewing the excitement around the record. Nobody wants to get it wrong. When there are 7,000 people proclaiming the Frank Ocean album a work of genius, who wants to be the voice in the wilderness saying otherwise? It was like that with Be Here Now. It almost felt inevitable: ‘This is a magnificent work of unparalleled rock majesty.’”

If the unforgiving reviews of the box set are any indication, the pendulum of received wisdom may never swing back in Be Here Now’s favour. It’s become an Aunt Sally for the sins of its era: a symbol rather than a piece of music. “Nowadays its reputation as one of the worst albums ever is as unfair as the hype at the time,” says Parkes. “It’s not even the worst album Oasis made. People might start listening to it again as a curio. There’s something really strange about it. It’s a fascinating historical document.”

Oasis Be Here Now (1997)

From stereogum.com

Be Here Now was the beginning of the end for Oasis. You know the story: Going into 1997, the Gallagher brothers were larger than life, unstoppable. In their native England, they were critically respected and massively successful commercially, having become the rock ‘n’ roll stars they once sang about becoming, but also becoming tabloid-fodder fixtures in the center of the era’s pop mainstream. They talked a big game, but they could back it up with the combination of Liam’s aura as a frontman — which was some unholy synthesis of force-of-nature vocals, laconic cool, and (then-amusing) boorishness — and Noel’s seemingly endless well of ingenious songwriting turns. Be Here Now didn’t just expose fallibility within Oasis — it veered right into it. The band was never quite the same, and their legacy was on its way to being cemented as an uneven one: generation-defining masterpieces in the beginning, followed by a jagged trail of oversized egos, streaks of mediocrity, and latter-day work that was surprisingly strong without being able to recapture the lightning-in-a-bottle moments of their Britpop youth.

Be Here Now was the beginning of the end for Oasis. You know the story: Going into 1997, the Gallagher brothers were larger than life, unstoppable. In their native England, they were critically respected and massively successful commercially, having become the rock ‘n’ roll stars they once sang about becoming, but also becoming tabloid-fodder fixtures in the center of the era’s pop mainstream. They talked a big game, but they could back it up with the combination of Liam’s aura as a frontman — which was some unholy synthesis of force-of-nature vocals, laconic cool, and (then-amusing) boorishness — and Noel’s seemingly endless well of ingenious songwriting turns. Be Here Now didn’t just expose fallibility within Oasis — it veered right into it. The band was never quite the same, and their legacy was on its way to being cemented as an uneven one: generation-defining masterpieces in the beginning, followed by a jagged trail of oversized egos, streaks of mediocrity, and latter-day work that was surprisingly strong without being able to recapture the lightning-in-a-bottle moments of their Britpop youth.

There was an uncontrollable, feverish anticipation ahead of Be Here Now, the likes of which scan as almost entirely illegible in today’s world. People lining up to the buy the album on release day, a label aggressively trying to control the album’s rollout but with actual power. It was something of a foregone conclusion that the successor to 1995’s (What’s The Story) Morning Glory? would, naturally, be another brilliant record continuing to define the times. Contrary to the reputation it’s accrued over the years, Be Here Now was initially, and briefly, met with hyperbolic praise. Backlash followed; there are anecdotes of record-store used bins supposedly filling up with quickly abandoned copies of the album.

In the two decades since, Noel has spent all sorts of time dissecting what went wrong. He’s spent time disowning the album outright, or saying they shouldn’t have made an album at all at that juncture, owning up to it being a work primarily inspired by cocaine abuse and runaway egos, or acknowledging that there could’ve been a record in there, if it could be reined in. At one point, there was some talk of re-editing the whole thing for a reissue, but Noel only got as far as opener “D’You Know What I Mean?” before giving up and/or losing interest.

Be Here Now was part of a larger moment in Britpop. After the genre’s heady peak in 1994 and 1995, when its principal artists all released the defining albums of the era, the late ’90s found the whole thing wavering as these same principal artists released albums that signaled Britpop’s depleted comedown. They took various forms, but the final ’90s releases from the major players were all big albums in some form — even Blur and Pulp, who made some of their weirder, darker, and most insular music during this era with albums like Blur, This Is Hardcore, and 13, were making long, sprawling works. Ancillary figures like the Verve and Spiritualized released albums like Urban Hymns and Ladies And Gentlemen We Are Floating In Space, albums overflowing with ideas.

Tonally, though, there’s something about Be Here Now that makes it a signature album of the times. Bloated and maximalist to a cartoonish degree, it was like the party that was so over-the-top that it almost necessitated the bleary-eyed companions provided by Spiritualized and Pulp and Blur. It’s the kind of album that highlights the end of an era because it essentially embodies the question “How can we possibly keep going on like this?”

Since its release, Be Here Now’s reputation has basically been that it’s an abject disaster. The reasons are well-catalogued at this point. Its blatant excess, the coked-out power trip of it all. It was one thing for Noel to brazenly storm out with Definitely Maybe and Morning Glory? when he had the arsenal of hooks to back it up. In comparison, many moments on Be Here Now feel overwrought in their hugeness but also vacuous and limp. The band sounds tired, even as they try to stampede through one of those albums that could only be made by people with too much money and too many resources (primarily of a chemical sort). Sometimes these moments in artist’s career can result in masterpieces, too, or at least flawed albums shot through with fractured brilliance that can earn them a cult status. But there’s a reason Oasis sound tired on Be Here Now — the bigness they’re trying to wield mostly settles into a murk, an overdriven flood of too much information fitting for the times but not in the most creatively productive way.??

The ways in which Be Here Now is overwrought are obvious. Every song is too long, sometimes excruciatingly so, sounding almost like a young band who simply doesn’t know how to end a song rather than someone who just thinks their shit is so good it needs to go on that long. The amount of random sounds and overdubs is ludicrous, pointless since it rarely adds anything, and sometimes detrimental given the added weight bogs down songs that should be able to move and impact more. It’s insane that a song like “Magic Pie” goes on for almost seven minutes when, stupid name aside, it could’ve had an effectively dramatic payoff in half that time. It’s insane that straightforward, hooky rock songs like “My Big Mouth” and “I Hope, I Think, I Know” seem to be fighting against themselves to keep up their pace, like ships that have taken on too much water. It’s insane that the final stretch of Be Here Now plays like Oasis is figuring out how to conclude the album, right there in real time, letting “All Around The World” drag on interminably, then switching gears to a rocker with “It’s Getting’ Better (Man!!)” and then — because why the hell not?! — going back to “All Around The World” for two more minutes. If everything had been edited just a little bit, it could’ve been as climactic a finale as the band intended, even with “All Around The World” barreling headlong into cloying Beatles-ripoff mode.??

And that gets at a subtler and more damaging shift Oasis underwent with Be Here Now, one that lasted through much of the rest of their career. When Noel first arrived on the scene, he was as indebted to the Smiths and Stones Roses as he was to the Beatles and Stones; he talked about how much he loved the Las and Love’s Forever Changes. But as moments like “All Around The World” evidenced, Oasis had become too enamored with the idea of themselves being in that classic rock pantheon.

Sure, Noel had jacked T. Rex riffs (among other things) in the past, but that fell under the old “genius steals” trope. Now, it felt like pastiche, between shamelessly Beatlesesque melodies and the overwhelming fixation on classic rock reference points littering the album. “Be Here Now” is a George Harrison song. Liam sings, “Sing a song for me/ One from Let It Be” on that same track. The Rolls Royce in the pool on Be Here Now’s cover references tales of the Who’s Keith Moon and his penchant for crashing expensive cars into pools. And the stacked Dylan/Beatles quotes in “D’You Know What I Mean?” (“The blood on the tracks, and they must be mine/ The fool on the hill, and I feel fine”) are embarrassing, the kind of wordplay a teenager might write upon first discovering those classic albums. Liam actually says “helter skelter” on “Fade In-Out,” another Beatles track that Oasis also covered. You know, in case you’ve missed the point.

Between that and their aging out — or, at least, Liam’s — into a caricature of what they once were, Be Here Now began the process of Oasis going from a vital young group to an establishment acting out ideas of the past. It was a quick process, with the band never really coming back entirely from the backlash against Be Here Now, their first two albums looming over everything they did in the future.

The thing that’s a shame about all this is that Be Here Now isn’t as bad as all that stuff would suggest. Amongst the tangled mess of it all, there are some real gems. “D’You Know What I Mean?” is representative of the album in many ways — the aforementioned lyrics, random sounds for no exact reasons (though the Morse code thing sounds kinda cool), and a mythologized amount of guitar tracks, supposedly numbering in the dozens. But it’s also a moment where Oasis running wild worked, a towering and enveloping opener ranking well amongst their history of strong openers.

“Fade In-Out” is a pretty uncharacteristic Oasis song — it sounds like a hallucinogenic experience in the American West — but the journey is worth it when the song crests into its most intense moments. (Plus, Johnny Depp plays slide on it, and this was back when Depp was still cool, so there’s a great bit of ’90s lore baked into the song.) The title track is a grungey sing-song overload, but it’s also infectious. If you can get past some of the inane lyrics — which, if you’ve gotten this far with Oasis, you probably can — it’s one of the most enjoyable songs on the album. There’s also the basic fact that Be Here Now is still a ’90s Oasis album, and even though it’s loaded up with all sorts of craziness, it’s still in that songwriting vein. That alone makes it better and more enduring than some of what’s come later.

Nevertheless, the high points and counter-narratives you can locate in Be Here Now were not enough to save the band from a fall from grace. They of course remained popular throughout their remaining years, and an Oasis reunion would no doubt be a big, headline-every-festival deal with many millions of dollars behind it. But the prevailing story, the established Oasis legacy for the moment, is that this was their Icarus moment. They got way too carried away, then crash-landed into a kind of holding pattern. Many fans write off anything that came after Be Here Now, which is unfortunate — there is worthwhile music from each of their albums, and they particularly rebounded in their latter years with 2005’s Don’t Believe The Truth and 2008’s Dig Out Your Soul. The ironic part is that those last two releases were more creative and legitimate interpretations of the classic rock canon than Be Here Now could have ever been. ??

Perhaps that’s because Be Here Now is also inherently a creature of the ’90s. Not only the turning point for Oasis or a warning sign of Britpop’s impending collapse, it’s also a blown-out rock album arriving at the end of decades of rock’s pop dominance. Of course, it’s not self-aware in that capacity. These were the halcyon days of the ’90s. Post-Cold War, pre-9/11, pre-recession. Bands like Oasis were raking in money from CD sales. There were resources, there was the newest cutting-edge technology.

This isn’t unique to music, either. Be Here Now is like the Star Wars prequels of classic rock. Sure, it might seem like a good idea to revisit the things that were great in decades past, now with new technology and new cultural movements with which to filter and play with it. That first Star Wars prequel — arriving two years after Be Here Now — is emblematic of an era of big-budget movies full of ill-advised CGI madness because it was the first time they could do that. In the same way, Be Here Now sounds like a big-budget flop, too, its overstuffed recording the equivalent of a movie laden with unnecessary special effects that don’t age well. It’s the sound of “because we can” not “because we should.” ??

When you add all that up, this is why Be Here Now sounds like a kind of last bellowing gasp of some idea of classic rock stardom. But it’s rooted specifically in the excess of the ’90s. The ’70s are full of double albums both deluded and radiant, they are full of albums with dramatic, expensive, drug-fueled origin stories that seem like pure fiction today. Yet there doesn’t feel as if there’s a direct precedent, in reality, for things like Be Here Now or other monuments of the ’90s where nobody was around to tell an artist they couldn’t or shouldn’t do something — whether that something resulted in rewarding works of respectable ambition (say, Smashing Pumpkins’ best albums) or whether it resulted in something like Be Here Now. This is the kids acting out a (maybe imagined?) cliché in rock’s final dominant hour. It’s fitting that Noel injected Be Here Now with so many classic rock references: The whole thing is like a final postmodern echo of some idea of the big, ambitious classic rock album, dressed up with contemporary bells and whistles that mostly amounted to clouding noise. ??

Here’s where Be Here Now, and Oasis in general, get consigned to layers of the past. The album was already portraying some received idea of classic rock excess. Twenty years later, it’s hard to imagine a respected and beloved band putting out albums anything like this — a not-insignificant reason being that the industry and the cultural landscape wouldn’t really allow for it on a practical level. Today’s rock bands, even the big ones, aren’t monolithic like Oasis were. Yet while means and atmosphere are factors, there’s also the issue of disposition. Can you imagine a rock band thinking and acting like Oasis today and being taken seriously? Can you imagine a rock band thinking they had the clout to burn, to the extent that they could even get to a point like Be Here Now? Overall, things are probably better in an era where rock artists are a little savvier, aware of the follies and pitfalls of their forebears. At the same time, there’s something transportative about a rock record like Be Here Now, something so over the top, so deranged and grandiose. It feels as if it only could have existed in that moment, in the late ’90s, making it a fascinating relic not just for the end of the Britpop era or Oasis, but for the pop decline of rock music as a whole.

Oasis Be Here Now (1997)

From pitchfork.com

Oasis’ third album from 1997 was always more circus than substance. The bloated and indulgent remaster only reinforces it as one of the most agonizing listening experiences in pop music.

The circus around Oasis’ third album, Be Here Now, makes the modern hoopla surrounding Frank Ocean, Kanye West, and Beyoncé look like amateur hour. Never was the hunger for new product greater, and never was the infrastructure designed to supply it in poorer shape. Back in the summer of 1997, the Manchester band’s label, Creation, and management, Ignition, were mobilized for battle, attempting to downplay the hype after months of tabloid chaos and over-saturation. Oasis had actually made another album, which should have been news enough.

The circus around Oasis’ third album, Be Here Now, makes the modern hoopla surrounding Frank Ocean, Kanye West, and Beyoncé look like amateur hour. Never was the hunger for new product greater, and never was the infrastructure designed to supply it in poorer shape. Back in the summer of 1997, the Manchester band’s label, Creation, and management, Ignition, were mobilized for battle, attempting to downplay the hype after months of tabloid chaos and over-saturation. Oasis had actually made another album, which should have been news enough.

Never mind that in September of ’96, Liam Gallagher had bailed on their diabolical MTV Unplugged performance before walking out on an American tour because, he claimed, he needed to buy a house. Two months later, he was arrested on London’s Oxford Street at 7.25 a.m. with his pockets full of cocaine, described by police officers as “an unkempt man, obviously the worse for wear.” The following January, Noel Gallagher left the nation clutching at pearls after declaring drug-taking to be as normal as having a cup of tea. The pair of them could barely leave their houses for the throngs of paparazzi camped outside.

The new record was also encumbered by what may have been the greatest millstone in pop music history: the double success of 1994’s Definitely Maybe and 1995’s What’s the Story (Morning Glory), which had already been minted as era-defining classics. You can see why the powers that be were trying to manage expectations. Journalists issued with a cassette of Be Here Now had to sign an absurd contract stating that they wouldn’t talk about the album while in bed with their partner. Ignition brought lawsuits against nascent fansites that carried any trace of copyrighted material. They called the police on three local radio stations that broke the embargo for lead single “D’You Know What I Mean?”, and pulled a raft of exclusive tracks from the BBC Radio 1 Evening Session after it was deemed that DJ Steve Lamacq hadn’t layered enough jingles over the songs to deter home-tapers. Even label staff were forbidden to enter the office at certain hours, lest they overhear the album, and at one point, Creation got a specialist in to check whether their phones had been tapped by Murdoch rag The Sun. It’s almost as if there were stratospheric amounts of cocaine involved at every level of the operation.

It might sound like damage control, but if anyone was engaged in that, it was the British music press. They had looked foolish after underrating What’s the Story (upon which Oasis played to 250,000 people across two nights at Knebworth), and were aware that Britpop’s luster was starting to tarnish. Every major news program sent a camera crew to regional record shops on the Thursday of release (MTV UK captured a young Pete Doherty in the queue in London), and HMV issued special certificates to first-day buyers. Magazine sales were predicated on their access to to the band, a valuable commodity that could easily disappear at the first sign of dissent, as evidenced by the album’s desperate and ingratiating reviews: “Oasis’ third LP is a veritable rock’n’roll monsoon of an album; a giant jigsaw puzzle, an elemental force, a monster that cannot and will not be contained,” claimed Vox. “Dem a come fe mess up de area seeeeeeeerious,” suggested Charles Shaar Murray in Mojo. Q actually called it “cocaine set to music,” which was about the only factual statement amid the lashings of hyperbole. Of the many cultural changes that Be Here Now triggered, the shift in power from the music press to marketing men may be the most toxic and enduring.

What sounded like a dog’s dinner in 1997 sounds no better on this 2016 remaster, which remains one of the most agonizing listening experiences in pop music. It’s not necessarily the songs—Noel Gallagher’s way with a hook is diminished, but passable enough to make “do you know what I mean, yeah yeah” feel sticky and semi-poignant. Even “Stand By Me” is genuinely touching. But the mix is gristle to Definitely Maybe’s fillet. There were reportedly up to 50 channels of guitar on each of Be Here Now’s tracks, sometimes coupled with a 36-piece orchestra, the effect evoking something like hell churning around a cement mixer, or agonizing indigestion. Aside from a two-minute reprise of a nine-minute song, the shortest track is 5:13. It boasts more key changes than a single series of “X Factor.” The morse code blips in “D’You Know…” supposedly spell out “bugger all.” A toilet appears to flush at the end of the title track. “In the first week, someone tried to score an ounce of weed, but instead got an ounce of cocaine,” said co-producer Owen Morris. “Which kind of summed it up.” After the two massive shows at Knebworth, there was nowhere left for them to go. The lyrics are jaded about success and filled with a foreboding sense that nothing’s set to last. (And they only add to one of pop’s greatest mysteries: How can two such naturally funny men be so bereft of lyrical talent?)

It’s easy to write off Oasis given what they became, but as the forthcoming documentary Supersonic makes clear, they were irresistibly magnetic in the early days. Their god-given wit and lack of inhibitions had even made traditional rock star excess into a guilty pleasure for fans who knew better than to buy into the cliche of throwing televisions out of windows. Be Here Now was the flipside of that Faustian pact, trading a generation’s communal optimism for empty calls-to-arms. Noel, at least, realized this and was doing down the record months prior to its August release. “It’s rocking but it’s not innovative,” he said in February ’97. “There’s no new ideas going on. It’s just us.” Within a few years, he admitted that he had been “making records to justify spending fucking thousands on drugs.” This reissue contains “NG’s 2016 Rethink” of “D’You Know What I Mean,” though that’s the only reworked track. “Someone (I can’t remember who) had the idea that we revisit, re-edit the entire album for posterity’s sake,” he said in a press release. “We got as far as the first track before we couldn’t be arsed anymore and gave up.”

So why bother reissuing a record so shit that it never even became a cult classic, that its warring creators can’t even be bothered with it? (Other than to flog £100 vinyl box sets, that is.) There are two-and-a-half hours of bonus materials here, few of them essential and most of them familiar: B-sides, demos, and live tracks—including the live debut of “My Big Mouth” at Knebworth, which somehow sounds better than the studio recording despite being recorded in the midst of a mob. Of most interest are the previously unheard and surprisingly fleshed out demos that Noel cut while on holiday in Mustique with Kate Moss and Johnny Depp (who plays slide guitar on grim blues pastiche “Fade In/Out”). In a sense, this turgid collection is the ultimate expression of Be Here Now: as bloated and indulgent as the record itself, the music a secondary concern to the product’s status.

It wasn’t just the end of Oasis’ imperial period, but the record industry’s as well. Ten days after the album came out, Princess Diana was killed in a car accident, shifting the national mood towards mass grief and mawkish sentimentality. Britpop receded to make way for a more humble kind of rock star in the likes of Travis and Coldplay. Although Oasis rightly questioned the absurd wave of national mourning, they also, in some backflip of contrarianism, started dedicating “Live Forever” to Diana at their autumn ’97 gigs. There was a lavish stage setup at these shows, with the band entering and departing through a giant phone box. The echoes of “Doctor Who”’s time-traveling Tardis were unavoidable: Oasis belonged to the past now.

Oasis Be Here Now (1997)

How do you follow up a multi-platinum masterpiece? The Beatles followed up Sgt. Pepper’s with the sprawling, flawed White Album. Fleetwood Mac followed up Rumours with the sprawling, flawed Tusk. And Oasis, that most classicist of Britpop rock bands, followed up (What’s The Story) Morning Glory with the sprawling, flawed Be Here Now.

Those first two follow-up records were double albums; this one is 71 minutes, close to double album length. It’s as if the band feels they have free reign to say whatever they want and that every note of it should be captured on vinyl. For a band with rampant egos such as Oasis, one can only imagine the spectacle and grandeur with which they would present their next slice of music…and Be Here Now does not disappoint on that level.

Four of the 12 songs here are around seven minutes long, one is nine minutes long and the rest are close to four or five minutes each, save for the closing instrumental coda. The music is blown up larger than life, with piles of instruments (guitars mostly), extended jams and long intros/outros that bloat this way beyond what it needs to be. Yet the hubris on display is exactly why people like Oasis in the first place, in essence making Be Here Now more of the same, albeit inflated to cartoon proportions.

“D’You Know What I Mean” starts things off with an airplane drone that crashes into the song, a swirling epic that is more about the production than the actual songwriting. Still, it sounds so good – and Liam Gallagher’s voice is as fine as ever – that it doesn’t really matter. As a leadoff single from the album, it was about as ballsy as one could get (7:41? Really?), but it’s pure Oasis.

Much of the swagger of this album comes from the band actually being the best instead of aspiring to be, the way they did on Definitely Maybe, so there’s a sense of invulnerability that pervades the music. Something like “My Big Mouth” would have fit in on that debut; here, it is given wall-to-wall guitar overdubs and played with absolute mid-tempo confidence. Actually, a lot of the songs are like that around the middle of the album, but none are truly memorable in the way the best early Oasis could be.

“Don’t Go Away” is one of the better songs, a relatively scaled back slower piece with some of Liam’s best singing to date and one that points the way the band’s music would eventually take from Heathen Chemistry onward.

The album closes with two epics this time around. The first is “All Around The World,” which starts slowly and continues to add on layers of sound (guitars, strings, brass Liam’s increasingly higher voice) for nine minutes, creating a soaring effect that sounds wonderful, even if it doesn’t have much to say or fails to create a mood the way “Champagne Supernova” did.

It would have been a fine album closer, but the seven minute “It’s Getting Better (Man!!)” gets that honor. Instead of a slow build, this one starts off loud and refuses to relent, even though it stays pretty safely hidden behind a wall of guitars the entire time. A change of dynamics would have helped, or some more chords, or maybe cutting out a couple of minutes and moving it up in the track listing.

The main problem with Be Here Now is not that it’s too much of a good thing, but that it’s similar to an Easter egg in that the delicious chocolate shell opens up to reveal a hollow inner core. Oasis didn’t have a lot of songwriting to do, so they instead piled on the sound to make what little they had sound good. It succeeds, but it leaves you feeling empty, and that ultimately keeps this from being the classic it so badly wants to be.

Oasis Be Here Now (1997)

Looking back at the mid 1990s, the British musical scene was rather different to what it is today. This was the era of Britrock, when Blur, Pulp, and many other bands ruled the charts. However, one band stood out above all these others, and is still thought of as the leaders of the genre in spite of the fact that it is generally thought that they peaked almost a decade ago with (What’s The Story) Morning Glory?. Hard as it may be to imagine now, for a period back then Oasis were not only the biggest British band, but also quite arguably the best.

When this album was released, it was one of the most ludicrously hyped albums in history already, to the extent that no matter what the band released, it was unlikely to be well received. This soon turned out to be the case, although it sold 250,000 copies in Britain alone on the first day of its release, and a total of 700,000 in less than a week. Critics, however, quickly seized on the album as overly long, and a bloated imitation of the previous Oasis. Crucially, the perception in the music world quickly became that Oasis had run out of ideas, something that they had never been accused of on their first 2 albums. Although these criticisms may have as much to do with public perception as to what the band should be doing, as to whether this album was any good, it’s undeniable that this doesn’t even come close to their previous work.

The songs:

1. D’You Know What I Mean immediately sets the tone for the album. Opening with the sound of a helicopter and a series of electronic noises, the song quickly becomes the type of arrogant rock song that Oasis had perfected on their first two albums. There’s a problem though. With the exception of the ballad Champagne Supernova, Oasis hadn’t recorded a song over 7 minutes before, as happens here, and they’re not the sort of band where epic songs work, largely due to their style, where most of their songs sound fairly similar, something which is at least partially on account of Liam’s trademark singing voice. As with quite a lot of songs on here, it would actually be a very good Oasis song if it were shorter. 3/5

2. My Big Mouth. This is one of the better songs on the album, with the kind of music and lyrics that could easily be imagined on Definitely Maybe. It’s got some more good lyrics, with Liam snarling, “Into my big mouth, you could fly a plane”, in a parody of himself and his arrogance, while at the same time refusing to apologise for this. The band also recaptures their guitar riffing ability here, making this a good Oasis song, without being a great one. 4.5/5

3. Magic Pie. This is where the problems really start. The first two tracks, although not brilliant, were quite good Oasis songs. Even this starts off well, with a softer Noel Gallagher vocal, but it quickly degenerates into a dirge of a song, which doesn’t seem to be heading in any real direction. The guitars are uninspired, as are the lyrics, with Noel seeming to be actually trying to force himself to show some emotion, and failing pretty badly at this. And of course, the fact that this is the third longest song at the album somehow makes the experience even worse, as at least D’You Know What I Mean and All Around The World have their redeeming features. This is Oasis at their worst, and is one to skip, adding a completely unnecessary jazz coda at the end. 1.5/5

4. Stand By Me. Well, it’s an improvement on the previous song, but this suffers from another of the album’s faults, namely that of overproduction. Oasis always worked best when their music sounded faintly in danger of veering off the road it was going down. Here it seems as if they were told by the record company what the song was going to be, and how it was going to sound. It’s not that bad a song though, with a good Liam vocal, and showing that the band possessed the ability to structure a song, although in this case it’s hidden under the layered guitars that lower this song. And sorry to beat a dead horse again, but this is just too long. 2.5/5.

5. I Hope, I Think, I Know. This is more like the old Oasis again, although it’s hard to escape the feeling that this would have been a filler track on one of their previous albums rather than one of the stronger points so far here. There’s nothing especially interesting or special about it, other than the fact that it features some pretty good drum work in the background, which really drives this song forward. This still gets 3.5/5 though for being both a definite improvement on what’s come before, and something that it sounds like Oasis put in more effort on.

6. The Girl In The Dirty Shirt. Although this is meant to be another Oasis ballad in the vein of Cast No Shadow, it, again, doesn’t come close. There are good moments in here, such as the vocals which show that while Liam Gallagher does not have a conventionally good singing voice, he can nevertheless really sing ballads well, but the instrumental section just seems to plod along, with the possible exception of Noel Gallagher, whose guitar seems fresh and more innovative than during other points in the album on here. This suffers from many of the same faults of the rest of the album, and gets 2.5/5.

7. Fade In Out. This song is one of the better points on the album for me, with a slow intro, which leads into a strong vocal over the band providing a surprisingly understated performance. It also has some of the better backing vocals here, and the band shows that they can be more than a one-trick pony when they want, with Liam’s scream leading into an instrumental break featuring some screaming guitars, again from Noel Gallagher. However, although the first section of the song is impressive and different, the hail of feedback and the repeated chorus it ends it leaves a sour taste in the mouth. 3.5/5.

8. Don’t Go Away. If track 6 was a disappointing Oasis ballad, this is far far worse. This song is absolutely cliche-ridden, with a string section grating in the background, the band staying resolutely in the background, and some dire lyrics, such as “Don’t go away, say what you say, say that you’ll stay, forever and a day”. It’s the kind of sentimentally unoriginal slush that fills the pop charts in the UK every week, and it’s disappointing to see that Noel Gallagher, a man that has written some truly great rock ballads (such as Live Forever, and the ubiquitous Wonderwall) has fallen to this level on this album. 1.5/5.

9. Be Here Now. As with other songs on here, nothing special, but there’s nothing specifically wrong with it either. The lyrics are total nonsense, but the overall feel of the song is OK, with an interesting keyboard riff played on a child’s piano. Although it sounds slightly stale, this is a solid Oasis song, and one that the band would have cruised through on previous albums. 2.5/5.

10. All Around The World. Something that is often said about Oasis is their love and admiration for The Beatles. This has never been more evident than on this track, which is their attempt at a Hey Jude style of song. While this is one of the most polarising songs on the album, I think it is the best thing on here by a long way. For a start, although it is very long, and again could usefully be cut, this is Oasis at near their best. A relatively simple song structure, and a message being confidently delivered by Liam, immediately makes this a bonus on previous tracks, although the orchestral arrangements in the background still annoy a bit. This would get 5/5, if it were shorter, as there is quite simply no need for this to be as long as it is. As it’s still the best song on here, and the one song I could recommend as a download, I’m giving this 4.7/5.

11. It’s Getting Better (Man!). As I’ve said before, with several other songs on here, its a decent song in it’s own right, without being anything special, but is too long, and doesn’t have the freshness that previous songs like this did. I’ve already written just about everything that could be used to describe this song in talking about Be Here Now, and I Hope, I Think, I Know, which should tell you everything you need to know about this song. 2.5/5

12. All Around The World (Reprise). In a word, why? This brings nothing to the album, featuring a full orchestra marching their way through the song, which, while good the first time, works rather less well for a further 2 minutes with no singing. This is a very weak end to the album, and provides further evidence of Oasis not being clear where they were going with this record, and, to a certain extent, not really caring that much. 1/5

There are several fundamental flaws with this album. As I’ve already said, not only could some songs easily be scrapped, but most of the songs on here could simply have a few minutes chopped at some point, to make this a tighter, more cohesive album. The band, more importantly, could have made a greater effort to recapture the energy and aggression that made them such a formidable force earlier in the decade, rather than resting on their laurels somewhat with this album. Although disappointment was perhaps inevitable for all the people who had been waiting for this album, such was the anticipation, this is an overly long album that has since been described by Noel Gallagher as “grossly offensive”, and the work of “two gobshites with a bag of charlie (cocaine)”. The album is fundamentally a tiresome listen, and one that you will not wish to return to on a regular basis, whether or not you like the band. Make sure you get Definitely Maybe, and (What’s The Story) Morning Glory?, but there’s no real need to bother with this.

Oasis Be Here Now (1997)

If the art of rock — and of making great rock records — is essentially a matter of putting the right notes in the right order over a good beat at top volume, then “D’You Know What I Mean?,” Oasis opening broadside on Be Here Now, is seven minutes of simple, focused genius. The important stuff is all here: the squealing feedback, chain-saw distortion and coughing wah-wah of a huge, brutish guitar orchestra; a slow, tough rhythm, stoked for extra measure by a drum sample from N.W.A’s Straight Outta Compton; a singer who ratchets up the cocksure posturing of the lyrics (“All my people right here, right now/They know what I mean”) with a sour howl and arrogant relish; a big finish in which everything in the mix — the guitars, the braying vocals, the fat whack of the rhythm section — is sucked into the jet-engine roar of the distended chorus.

There are references to God in the lyrics, and the song appears to be about a crisis of faith. But you wouldn’t know it from the attitude pouring through the amps. “D’You Know What I Mean?” — and for that matter the rest of Be Here Now — is music built for impact, not explanation. You want epic narrative, grand metaphor and explicit spiritual testimony? Get a book of poetry — or a Van Morrison record.

Oasis are not, and have never been, a complex listening experience; in fact, they’ve basically made the same album thrice. Like 1994’s Definitely Maybe and 1995’s (What’s the Story) Morning Glory?, Be Here Now is ’60s and ’70s rock classicism writ large and loud, all broad strokes and bullish enthusiasm. As the band’s songwriter, co-producer and (for all intents and purposes) iron ruler, guitarist Noel Gallagher doesn’t spend any sweat on highbrow drama or intellectual pretense.

He fires up sing-along hooks with industrial-strength glam-rock licks; he drapes his words and music in the reflected splendor of the Beatles at every available turn, mostly through song — and album-title references, and spit-shines the results with a kind of roughneck sentimentality, heard to most obvious effect in the Sunday-night-pub-chorale endings of “Magic Pie” and “All Around the World.”

It’s a formula that can go either way: brilliant, steel-plated consistency or vacuous, shopworn predictability. Gallagher and Oasis pull it off, in great part, because they do not concede any possibility of fucking up. A lot of Gallagher’s lyrics are catch-phrase cocktails of youthful optimism and hard-boy temperament: “Comin’ in out of nowhere/Singing rhapsody” (“Fade In-Out”); “Into my big mouth/You could fly a plane” (“My Big Mouth”). But the most contagious thing about buzz bombs like “My Big Mouth,” “I Hope, I Think, I Know” and “It’s Gettin’ Better (Man!!)” is the sheer physical confidence of the music, particularly in the tandem rock ribbed guitars of Gallagher and Bone-head (a k a Paul Arthurs), and the way singer Liam Gallagher literally assaults the songs written for him by his older brother.

Much has been made of the John Lennon factor in Liam’s nasally, brattish intonation. In fact, his voice is a flat, thin thing. What’s remarkable about it is its emphatic, almost fighting quality; Liam enunciates Noel’s lyrics with snappish irritation and grinds the vowels in words like fade and away into high-tension whines. By the time Liam gets done with the chorus in Noel’s Big Melodrama ballad, “Stand by Me” — “Stand by me-e-e/Nobody kno-woa-ahs/The way it’s gon-nah-h be-e-e” — it sounds full of portent, if not bona fide linear meaning.

The payoff in Noel’s writing is always in the choruses; all riffs, hooks and bridges lead there. So Noel feeds Liam words and phrases that, above all, sound good. While it’s hard to excuse jury-rigged verse like “A cold and frosty morning/There’s not a lot to say/About the things caught in my mind” (“Don’t Go Away”), sometimes in pop music, melody, muscle and mouthing off can be their own substantial reward.

But only for so long. Oasis can’t rely on this Abbey Road-meets-Never Mind the Bollocks routine forever. There are already signs of strain on Be Here Now. “Stand by Me” is a little too close to Morning Glory’s “Don’t Look Back in Anger” for coincidence, and there is an overreliance on swollen “Hey Jude”-style finales in the ballads.

Which brings up the Beatles issue. Noel Gallagher’s love of the group is genuine. “Sing a song for me/One from Let It Be,” he writes in “Be Here Now” — a title cribbed from Lennon’s infamous quip to an interviewer who asked him about the deep, underlying philosophy of rock & roll. But Noel is starting to overplay his hand; dropping a line like “The fool on the hill and I feel fine” in the middle of “D’You Know What I Mean?” smacks of laziness more than fannish ardor.

Maybe if Oasis weren’t so ultra-mega-huge in England and smiled more onstage when they came here, it would be easier to accept them for what they are: a great pop band with a long memory. What will they, or their records, mean in 20 years’ time? Who cares? Be here now. History will take care of itself.

THE CASSETTE COLLECTION HAS MISLABELED THE SONGS ON TAPE NUMBER THREE. THE 1ST SIDE ENDS WITH LAY DOWN SALLY....NOT THE…